This post is more personal than most as it is an account of an ancestor who served at the Battle of Waterloo. Until my father researched our family history, we had no idea that a relative had served at the battle, or that his name had been commemorated down the generations, up to my brother.

No. 100 Private Richard Jones is listed on the Waterloo medal roll as having served with Captain Eeles’ Company of the 3rd Battalion, 95th Regiment, and his service record states that he served two years in ‘Holland, France and the Netherlands.’ There are no accounts by him of his experiences at the Battle of Waterloo but they may be pieced together from a description left by his company commander, William Eeles.

Richard Jones was born in 1796 in the parish of Whitfield, near Dover, Kent. On 22 May 1813 he enlisted at Deal for the 95th Regiment; he was aged 18 and his occupation was given as labourer. Unlike most other infantry regiments, the 95th was armed with the Baker rifle, a more accurate and longer range weapon than the smooth bore Brown Bess musket. Riflemen were usually employed in advance of the infantry, in more widely dispersed ‘skirmish lines’ and were trained to act independently. Rather than the traditional red coat, they wore dark green.

British Army Riflemen of the 60th and 95th Regiments, 1812. J C Stadler, from Charles Hamilton Smith’s ‘Costumes of the Army of the British Empire’ (National Army Museum).

In November 1813, as Napoleon retreated into France, the British tried to secure possession of the Scheldt estuary and two companies of the 3rd Battalion of the 95th, commanded by Captains Fullarton and Eeles, left Shorncliffe to form part of an expedition to Holland under Sir Thomas Graham. Richard Jones will have seen action at the capture of Merxem on 2 February 1814, when three officers of Eeles’ Company were wounded, including William Eeles himself. In March, the Allies captured Paris, Napoleon abdicated and was exiled to the island of Elba. Fullarton and Eeles’ Companies formed part of an Anglo-Hanoverian force which remained in the newly-established Kingdom of the Netherlands.

In April 1815, however, following Napoleon’s escape from Elba, the two companies, under the command of Colonel Ross, were sent to join the army of the Duke of Wellington in Belgium which was preparing to halt a march by Napoleon and his army on Brussels. The two companies were posted to the 3rd (Light) Infantry Brigade, commanded by General Sir Frederick Adam, which comprised the 52nd Light Infantry, the 71st Light Infantry (Glasgow Highlanders) and also the 2nd Battalion of the 95th. Eeles’ Company was to work in concert with the 71st. Part of Sir Henry Clinton’s 3rd Division, Adam’s Brigade was to fight on the on the right (west) of Wellington’s line in the coming battle of 18 June 1815.

Throughout the morning it remained in reserve behind a ridge. At about midday Napoleon’s guns opened fire and Wellington’s responded. Adam’s Brigade moved forward through dense smoke from the artillery fire but waited behind the ridge, just out of sight of the French, while the artillery bombardments continued. Some of Adam’s Brigade were hit by cannon balls coming over the crest but Eeles’ riflemen suffered no casualties and could see nothing of what was going on. They were unaware that Napoleon’s infantry were advancing against their left and pushing the British line back, only to be themselves forced back by a British cavalry charge.

At about 4pm, the French Marshal Ney renewed the attack, sending first cavalry and then infantry to try to break Wellington’s centre. Wellington ordered Adam’s Brigade forward over the ridge. Moving ahead in column, the 71st and Eeles’ riflemen could see nothing amidst the smoke until, suddenly, it cleared and the 71st found itself facing a very large number of French troops formed in line. The 71st immediately had to form line in order to bring its musket fire to bear. Eeles, who had never seen troops engage one another at so close a distance, also successfully got his Company into line on the right of the 71st but both units suffered severely from the French fire. Immediately they were formed into line, however, they repulsed the French who disappeared into the smoke. But Eeles’ men and those of the 71st were still falling from musket shots and so Eeles moved his Company forward and found a considerable number of French firing at them from a depression in a rye field. Eeles and his men immediately opened fire on them, driving them back to their main position on a hill but, at that moment, he noticed a mass of French cavalry advancing towards them. At the sight of the cavalry, the units of Adam’s Brigade formed into squares and Eeles men were just able to retreat to safety behind the square formed by the 71st before the French cavalry attacked it with, Eeles recalled, ‘much impetuosity and determination.’ However, the 71st received the charge ‘with the utmost coolness and gallantry.’ The French horsemen repeatedly tried to break the squares but each time were repulsed ‘without the least loss or disorder.’ Other units of Adam’s Brigade suffered during these attacks and when Colonel Ross, commanding the 3rd Battalion 95th, was badly wounded, Major Fullarton took over command; when Fullarton was severely wounded about an hour later, Eeles found himself in command of both companies. During one of the attacks, when French cuirassiers charged against the right of the 71st’s square, Eeles moved his men out in line with the rear face so that they could bring their accurate rifle fire to bear on the attackers. He stood in front of his men and made them hold their fire until the cavalry were within thirty or forty yards, then ordered the volley. Instantaneously the charge was completely halted as the leading horses and riders collapsed to the ground and those behind tumbled over them. It seemed to Eeles that half of all the horses and men came down: ‘by far the greater part were thrown down over the dying and wounded. These last after a short time began to get up and run back to their supports, some on horseback, but most of them dismounted.’ This, he said, proved that it was impossible for cavalry to charge infantry ‘if the Infantry will only be steady, and give their fire all at once.’

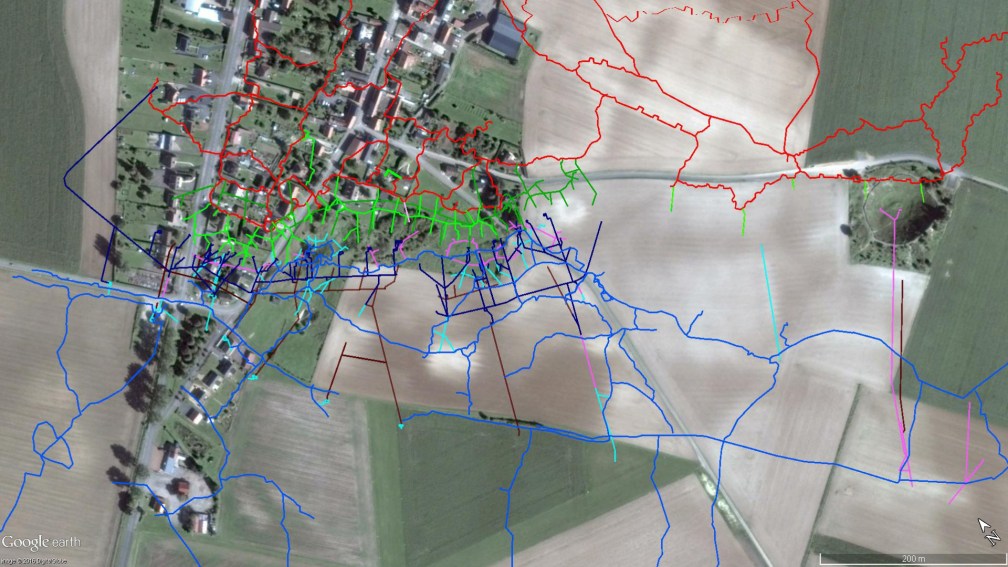

Map from Siborne’s Waterloo Letters, showing the movements of Adam’s 3rd Infantry Brigade. The positions of 3rd Bn, 95th Regiment highlighted in green.

After beating off the cavalry attacks, Adam’s Brigade remained in squares. The riflemen’s position to the right of the 71st placed them immediately next to the outer perimeter of a farm called Hougoumont, for which there was heavy fighting for much of the day. However, once the French cavalry withdrew, their guns opened fire on the squares while a large mass of French cavalry waited on the hill opposite. Eventually, Adam’s Brigade was moved back behind the shelter of the ridge and formed in line ready to fire into the left flank of an expected attack by Napoleon’s infantry against the centre of Wellington’s line. Eeles’ men, behind the 71st on the far right, could again see nothing of what was happening but heard the British guns open fire. Then the infantry of Adam’s Brigade fired off a musket volley and moved forward to the advance, with Eeles’ men following.

What they could not see was that Napoleon had sent his Imperial Guard to attack. It had never been defeated in battle and no troops were supposed to be able to withstand its advance. Advancing in a column sixty men abreast, it veered towards Adam’s Brigade and, to meet it, the 52nd Regiment moved out to bring its muskets to bear on the left flank. The Imperial Guard column halted, turned its left sections to face them, and opened fire, causing heavy loss to the 52nd but the Colonel of the 52nd then ordered his men to charge. General Adam galloped to the right of his line to order the 71st and Eeles’ riflemen also to move into line and open fire. But by this time the 52nd was already charging and, according to one of its officers, within ten second the Imperial Guard column broke into the ‘wildest confusion’ and began falling back.

As the 52nd and 71st Regiments advanced, Eeles was able to bring his riflemen forward into a gap which opened between them. When the smoke cleared a little, he saw that they were moving between the two armies and ‘driving some French troops before us in the greatest disorder.’ He was quickly ordered to take his riflemen out in front to form a skirmish line and advanced until cavalry, English, German and French, forced them back between the 52nd and 71st, where they were squeezed in with Fullarton’s Company. They continued the advance in ‘close and compact order’ for half a mile until Adam’s Brigade reached troops of the Imperial Guard formed in three squares. Wellington ordered Adam’s Brigade to attack the squares whereupon the Imperial Guard fired, then retreated once more.

As the French retired, the two companies now commanded by Eeles were again sent forward as skirmishers and pursued the fleeing French ‘as fast as they were able’, eventually reaching houses a mile away at Rossomme Farm. Eeles was wary of a French attack but found no enemy left: ‘They had all gone off in the dusk of the evening…’ The battle was won.

Only later would Eeles discover that his brother Charles had been killed during the battle while serving as Brigade Major to Sir James Kempt. The 3rd Battalion of the 95th was amongst the first troops to enter Paris in July 1815, and remained encamped on the Champs Elyseés until October when it moved to Versailles. In 1816 the 95th Regiment was renamed ‘The Rifle Brigade’ in recognition of its performance of its specialist role.

Richard Jones continued to serve with the 3rd Battalion on its move to Dublin, until its disbandment in 1818 when he transferred to the 2nd Battalion. In 1826 his battalion sailed for Malta, where he spent six years, followed by two years in the Greek or Ionian Islands. His discharge was set in motion while he was at Corfu and he left the army on 30 April 1834. He had served 20 years and 344 days, just short of the 21 years needed to qualify for an army pension. However, soldiers who had served at the Battle of Waterloo had their pensionable service increased by an extra two years, thus rendering him eligible. His rank remained that of private and so his pension would not be great. On leaving the army he was 39 years of age, five feet nine and three-quarter inches in height, with brown hair, grey eyes, a fresh complexion and was described as in good health. He returned to his place of birth, Whitfield, just outside Dover, to join his brothers and sisters at Pineham, where they worked as farm labourers. He never married, but resided with the family of his younger brother William. He outlived many of his brothers and sisters and, after William’s death in 1857, lived with his brother’s widow Harriet until she died in 1874. In the 1861 census he was described as a Chelsea Pensioner, (that is, an army out-pensioner) and Harriet was listed as a ‘pauper’. Only in the last two years of his life, shortly before Harriet’s death, was there any increase to his pension, stated variously in newspaper reports as having increased from six or ten pence a day to one shilling and six pence or ten pence but according to his service record it rose in 1874 to one shilling and six pence. By the time of his death, age 81 on 11 November 1876, veterans of Waterloo were rare enough for the event to be widely reported in the press across Britain.

The Luton Times and Advertiser, November 1876.

On 18 November The Whitstable Times and Herne Bay Herald printed a tribute which paints a picture of the aged veteran still proud of his service, joining with soldiers as they marched to and from the Dover garrison:

DEATH OF A WATERLOO VETERAN.- Death has just carried away, at the ripe old age of 81, the only Waterloo veteran Dover possessed. His name was Richard Jones, living in Peter Street Charlton. He had served in the Rifle Brigade, and besides being present at the battle of Waterloo, was in many other engagements. Until recently the old gentleman might be seen taking part in the marches of the troops of the garrison whenever they passed through that district, and it was pleasant to see him striding along erect and martial like with the younger soldiers. The sound of the band was sufficient to draw him from his house, and he might be always seen at the corner of Peter Street waiting for the approach of the troops. His pension was originally 10d. a day, but through the kind offices of Mr. John Clark, of High Street, it was increased to 1s. 9d. Deceased was brother of Sergeant Jones, formerly of the South Eastern Railway.

That the name Richard recurs in the descendants of his siblings cannot be a coincidence: every alternate generation of descendants of his brother James has been named Richard. However, by the time my elder brother was named Richard after his grandfather in 1962 the association with his 3rd great grand uncle had been forgotten. Only with the family history research of our late father was this continuity rediscovered.

Simon Jones, 17 June 2015

Sources:

National Archives WO97/1081 Army discharge record

National Archives WO100/15b Waterloo medal roll

Cope, The History of the Rifle Brigade, (London, 1877).

T. Siborne, Waterloo Letters, (London, 1891).

Join me on a battlefield tour with The Cultural Experience:

The War Poets: Words, Music and Landscapes, 10th-13th July 2023

First & Last Shots 1914 & 1918

Medics & Padres in the Great War

Walking the Somme, Summer 2023

More Information about Battlefield Tours

Myths of Messines: Four Misconceptions about the 1917 Battle Re-examined

Yellow Cross: The Advent of Mustard Gas

![British_55th_Division_gas_casualties_10_April_1918[1]](https://simonjoneshistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/british_55th_division_gas_casualties_10_april_19181.jpg?w=1008)

Dear Simon,

What a fascinating story, and the research for this must have been really interesting for you, what with the personal interest. Really good of you to share it today.

Ken

Thanks for sharing that Simon. Very interesting.

Excellent read, thanks. I discovered this weekend that my great x4 grandfather (also from Kent) was also in the 3rd Battalion of the 95th at Waterloo. He also left the Army in 1834, and died in 1878. Wonder if they knew each other…

That’s amazing news! I hope they did know each other and were able to keep in touch. Have you checked the online newspapers for mention of his death? I have a subscription if it helps.

I’d like to think so! I have searched the newspapers on Findmypast, but couldn’t find anything. His name was Henry Hammond, born in Harbledown (although his Army records say it’s Arbledown), near Canterbury. Harbledown is only 16 miles from Whitfield. In later years, he lived in Temple Ewell, which is about 2 miles from Whitfield. He then went to Canterbury in his last years. At Waterloo, he was in Captain Fullerton’s company.

Thank you Russell, that’s very interesting, I hope something turns up in the newspapers.

Hi Simon. I served for over 23 years in the Royal Green Jackets so I found this story extremely important & interesting as part of the history of our regiment. Why not contact our Regimental Museum in Winchester & give them the story. The whole of the top floor is dedicated to the battle of Waterloo. I believe the account would add greatly to the collection. Of course Richard is a direct relation to you but Richard has also a much larger family being s fellow Rifleman. Richard has thousands of brothers within the regiment today. I would think now the local RGJ Association know where he is buried they will honour him each year on Remembrance Sunday. If you still live in the area then why not pop along & see the guys. Best wishes Neil

Thank you Neil, I am glad that you enjoyed the article and am grateful for your comments. I’ve never been able to investigate whether his grave survives at Dover and have contacted the RGJ Museum via Twitter, so perhaps that will lead to a discovery. I visited the Museum in Winchester many, many years ago and hopefully will return this year. best wishes, Simon

Hi Simon, If you live close to Dover then why not attend the remembrance service outside the town hall. The guys meet at the Dover Sea Angling Club before the event then directly afterwards we go to our war memorial just off the sea front to lay reaths there. The memorial is not for Waterloo it’s for the Indian Mutiny but we use it to remember all that have fallen over the years to present day. If you go from the market square towards the sea front on foot you will see an underpass for the main road to the docks. As you come out the other side you will see the memorial directly in front of you. I hope this is of some help mate? You never know we could meet on the day! King regards Neil

Thanks Neil, Sounds like a very good ceremony. I’m a fair way away in Windsor but perhaps one day! regards Simon

Great article!

Thanks Josie!

This is a great find for me Simon. My ancestor (William Edwards), a native of Sussex, served under Eeles that day having joined the Peninsula Wars with the 95th Foot in 1809. He was wounded in the hand and chest at Waterloo- and was said to be buried (in 1864) with a musket ball still in his chest. William emigrated to the new colony of Western Australia in 1830.

To get such a concise breakdown of the day’s events is awesome, will be sharing with the clan down-under.

Hi Dominic, that’s great to hear and really fascinating.

Hello Simon, and other readers. I hope you are still running this discussion on the 3rd battalion of the 95th in 2023? An ancestor of mine, James Norris, from Sedgehill in Wiltshire, I am hoping is the soldier by that name in Captain Eels’ company at Waterloo (as a corporal) and was later in Dublin for 2 years (as a sergeant), then at Birr in co. Offaly until the end of 1818 when he was discharged. His son William was born ca.1817 in Ireland according to the 1851 census, and his father matches the tradition in our family that we had an ancestor at Waterloo. I have been looking for some years for any source that would document a soldier’s marriage in Ireland (Dublin presumably) after the arrival of the 3rd battalion. James died back in Wiltshire in 1842 of consumption, and his widow Mary died in Winchester in 1849. I don’t know her surname, and as she didn’t live until the 1851 census, I can’t track her place of birth. Does anyone have any ideas? I have all the muster rolls for James Norris from his first service with the Wiltshire Militia, to his transfer to the 95th, and his later time in Ireland. It’s a very fascinating thing to have a Waterloo ancestor – if I can prove it! Somewhere in England (but not South Australia, where I live) there may be a descendant who still has James Norris’s Waterloo Medal after over 200 years.

Thank you for your comment Neil and good luck with your quest for more information about James and Mary.