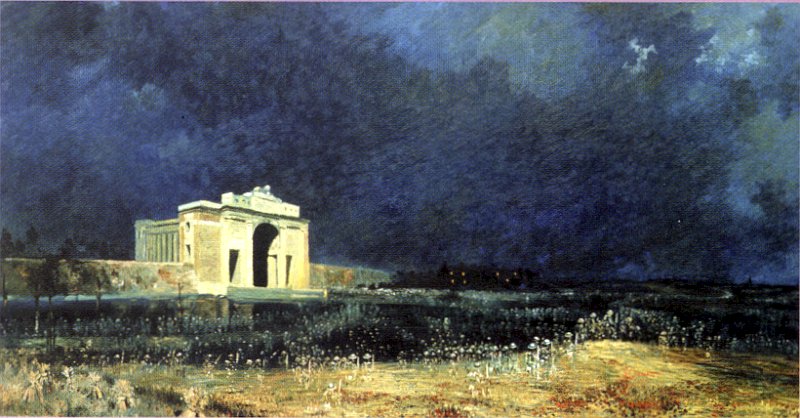

Over the past fifteen years, an anonymous poem has grown in popularity, especially with battlefield visitors who find that its sentiments strike a chord with them as they attend the evening sounding of the Last Post at the Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium. The memorial, unveiled in 1927, bears the names of more than 54,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers killed in the Ypres Salient who have no known grave.

The poem appears to have been inspired by the Australian artist Will Longstaff’s painting of 1927 ‘Menin Gate at Midnight’ which shows the ghosts of the dead filling the battlefield around the newly built memorial. Entitled ‘Man at Arms’, the poem is always described as by an anonymous author. The writer addresses a soldier who tells how, just as in the painting, the dead will rise at midnight and march to the Menin Gate.

Man at Arms

What are you guarding, Man-at-Arms?

Why do you watch and wait?

‘I guard the graves, said the Man-at-Arms,

I guard the graves by Flanders farms

Where the dead will rise at my call to arms,

And march to the Menin gate’.‘When do they march then, Man-at-Arms?

Cold is the hour – and late’

‘They march tonight’ said the Man-at-Arms,

With the moon on the Menin gate.

They march when the midnight bids them go.

With their rifles slung and their pipes aglow,

Along the roads, the roads they know,

The roads to the Menin gate.‘What are they singing, Man-at-Arms,

As they march to the Menin gate?’

‘The Marching songs’, said the Man-at-Arms,

That let them laugh at fate.

No more will the night be cold for them,

For the last tattoo has rolled for them,

And their souls will sing as of old for them,

As they march to the Menin gate.

Popular as it has become, I have never included it in my literature and art battlefield tours because I had no evidence that it was the authentic testimony of someone who had experienced the war. Curiosity as to its origins however led to research its authorship. Jeffrey Richards in Imperialism and Music: Britain 1876-1953 (2001) quotes the opening lines as being from a song The Menin Gate by Bowen. This proves to have been by Lauri or Lori Bowen, published in 1930 by Boosey & Hawkes, with words by Eric Haydon. A recording performed by Peter Dawson was released by His Master’s Voice in 1930.

![[Gen Charsley] EeAHyX_XgAUZi8x-ROT2-cr](https://simonjoneshistorian.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/gen-charsley-eeahyx_xgauzi8x-rot2-cr.jpg?w=469&h=467)

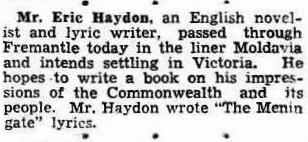

The 1930 His Master’s Voice recording of ‘The Menin Gate’ by Peter & Herbert Dawson was credited to the composer Bowen but not the lyricist Haydon (Courtesy of Genevra Charsley).

The Perth Daily News, 28th January 1936, announcing the arrival of Eric Haydon.

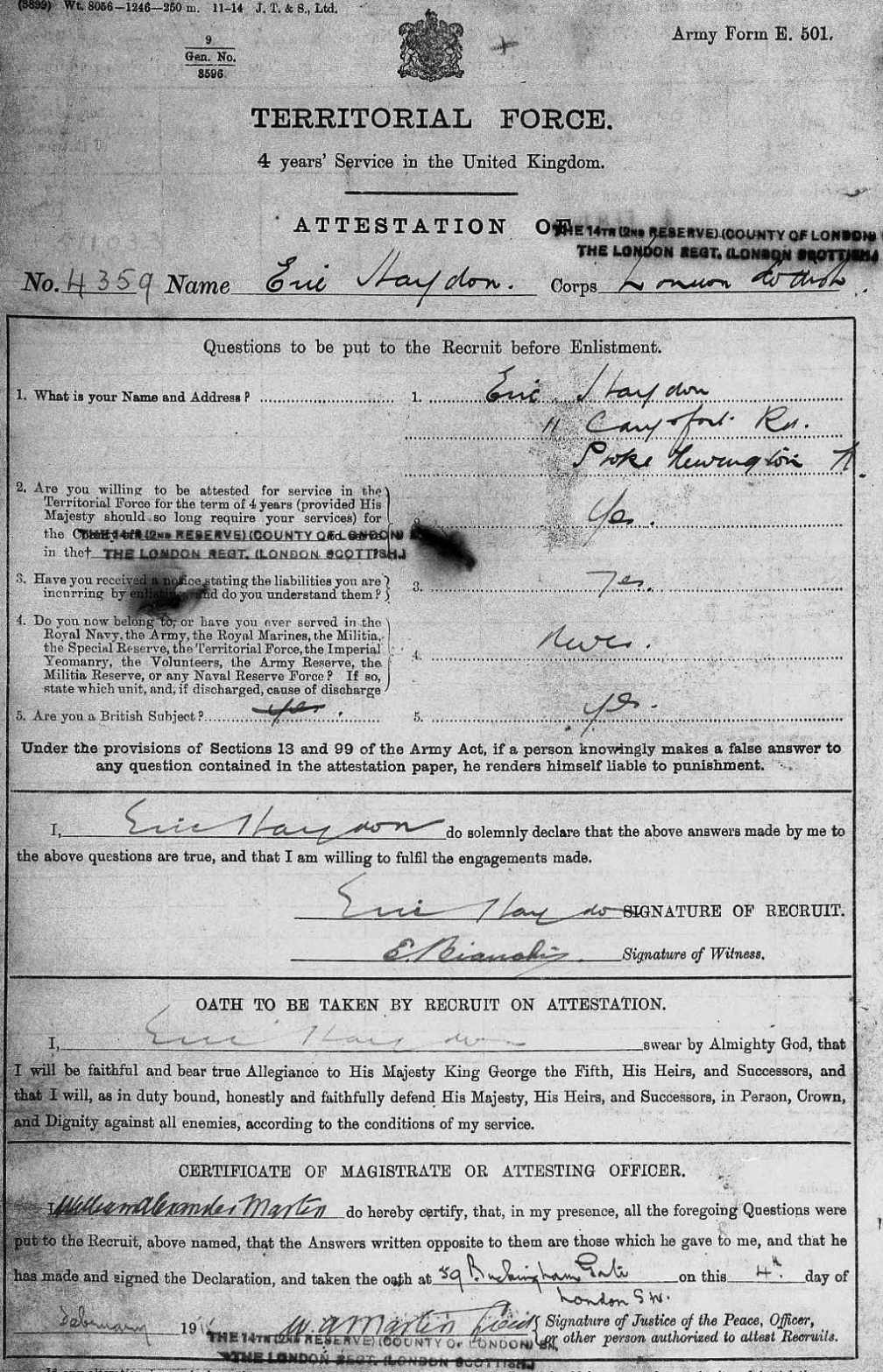

The passenger list of the Moldavia includes Eric Haydon, age 42, en route for Melbourne, having previously lived at an address in London NW3. Census returns and a 1939 militia attestation form show that he was born in Kensington, London, on 7 July 1895, the son of a cheesemonger’s assistant. By 1911, age 16, he worked as a cashier’s clerk for a publisher and lived in Stoke Newington. In the 1930s, Haydon began to have some success as a song lyricist and novelist. In September 1939, when he enlisted in the Australian Militia, he lived at 30 Tivoli Road, South Yarra. Success however brought mixed blessings as the award for the best radio play in Australia of 1947 unfortunately seems to have drawn his financial affairs to the attention of tax officials who the following year fined him £70 for having failed to declare income from the play. He died in Parkville, Victoria, in 1971 at the age of 76.

There remains the question as to whether Eric Haydon’s experiences during the First World War might have inspired the lyrics to ‘The Menin Gate’. Luckily, a service record survives enabling his military career to be reconstructed. In February 1915 Haydon enlisted as a Private in the London Scottish, number 4359, and was posted to the 2nd Battalion with which he served for the whole war.

Eric Haydon’s attestation form showing his enlistment in the London Scottish on 4th February 1915. (National Archives WO363)

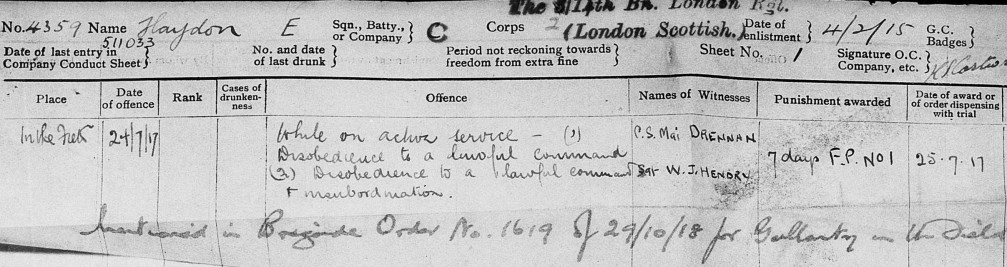

This battalion was to have a remarkably varied experience, being posted from Salisbury Plain to Ireland in April 1916 in the wake of the Easter Rising, then to the Western Front where it spent time on Vimy Ridge. After five months in France, it was sent to Salonika (Thessaloniki) in Greece, then seven months later, in July 1917, to Egypt. It was at this point that the one misdemeanour contained on Haydon’s crime sheet occurs, when he was found guilty of disobedience to a lawful command and insubordination resulting in a sentenced of seven days Field Punishment No. 1, the infamous tying of a soldier to a fixed object for several hours each day in place of detention in the guardroom. The 2nd London Scottish spent ten months in Palestine, where it took part in the capture of Jerusalem in December.

Eric Haydon’s Crime sheet showing the award of 7 Days Field Punishment Number One in July 1917 and his mention for gallantry in October 1918. (National Archives WO363)

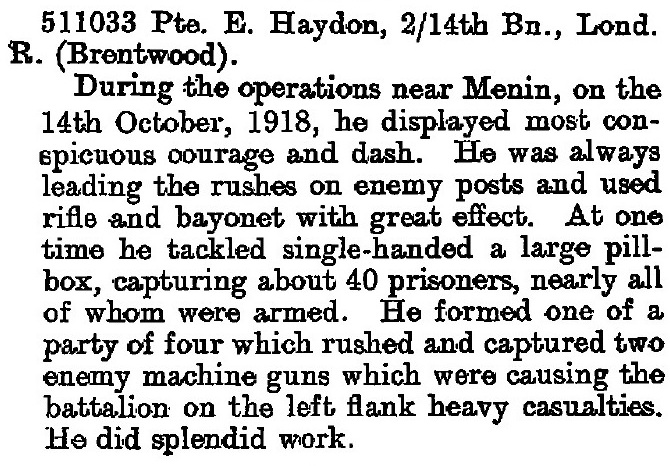

The German attacks in the Spring of 1918 led to Haydon’s battalion being sent to the Western Front in June: it is at this time that he would have first seen the future site of the Menin Gate at the eastern exit through the Ypres ramparts on the route taken by troops to the front line. At the end of September his battalion retook Messines, then participated in a final advance, the forgotten ‘5th battle of Ypres’, to push the Germans back from Ypres and which by mid-October 1918 resulted in the Battle of Courtrai. During this fighting he was mentioned in a Brigade Order for Gallantry in the Field. This resulted in the award of the Distinguished Conduct Medal, announced in the London Gazette of March 1919. It wasn’t until December 1919 that the citation was additionally published which reveals an astonishing action which in the earlier years of the war would have gained him the Victoria Cross:

Eric Haydon’s citation for the Distinguish Conduct Medal, published in the London Gazette, 2nd December 1919.

Private Eric Haydon was discharged in February 1919 unscathed physically by enemy action with a total of four years and 20 days service.

I can now include his poem in my tours as an authentic testimony by one who saw Ypres in its most devastated state, and who played a remarkable part in the fighting in the last days of the war.

Listen to the Peter Dawson recording of Bowen’s song Menin Gate here (from a web page by Roger Wilmut).

Note: I’ve since discovered that Major & Mrs Holt’s Battlefield Guide to Ypres Salient and Passchendaele (Pen & Sword, 2011 Ed.) credits Eric Haydon as the author and acknowledges Martin Passande as the source.

Join me on a battlefield tour with The Cultural Experience:

The War Poets: Words, Music and Landscapes, 6th-9th July 2023

First & Last Shots 1914 & 1918

Medics & Padres in the Great War

Walking the Somme, Summer 2023

More Information about Battlefield Tours

Myths of Messines: The Lost Mines

Myths of Messines: The Lost Mines

Understanding Football and the 1914 Christmas Truce

Well done Simon Jones and may I be the first to congratulate you about your “first post”.

Thank you Simon. Much appreciated. My first post was on the Last Post!

Congratulations Simon. It is a superb poem and I often wondered who the author was!

Thank you Chris. I’ve replied on the Great War Forum and added the amazing DCM citation.

The popularity Australia might also be because Peter Dawson was Australian – he was something of a star even thought he specialised in these sort of songs. His recordings of ballads, comic songs, classical pieces and hits such as Floral Dance and Road to Mandalay were very popular. Clancy of the Overflow is worth looking out.

While the words are not great the setting and the performance are quite remarkable and very moving.

Thank you Nigel!

Great research. Always fun to do and always great to read.