How was it that in 1955 a massive mine charge blew up in a Belgian field? When nineteen mines were detonated along a six mile front at the opening of the Battle of Messines on 7 June 1917, six more huge explosive charges totalling over 80 tons were left to lie dormant and forgotten deep beneath the battlefield. For decades, until the records in the British archives were examined, the number of ‘lost’ mines and their location remained unknown.[1]

Troops on the rim of one of the Messines mine craters, probably Peckham, shortly after the battle. (Imperial War Museum Q 2325)

Abandoned: the Birdcage Mines

The charge that went off was in fact one of four, planted close together on the far southern flank of the attack front. Laid with great effort by miners of 171st Tunnelling Company, they were at the end of two 700 feet long tunnels beneath a German salient known as the Birdcage which jutted towards the British lines. The charges of 20,000, 26,000, 32,000 and 34,000lbs, laid at between 65 and 80 feet depth, were designed to utterly destroy the Birdcage. Laid in the spring of 1916, they were intended for an the attack on the Messines Ridge originally projected to take place in June. But this attack, already scaled back after the German assault at Verdun, was postponed when the decision was taken in July to continue the Somme attack. The Battle of Messines was not to take place for another year.

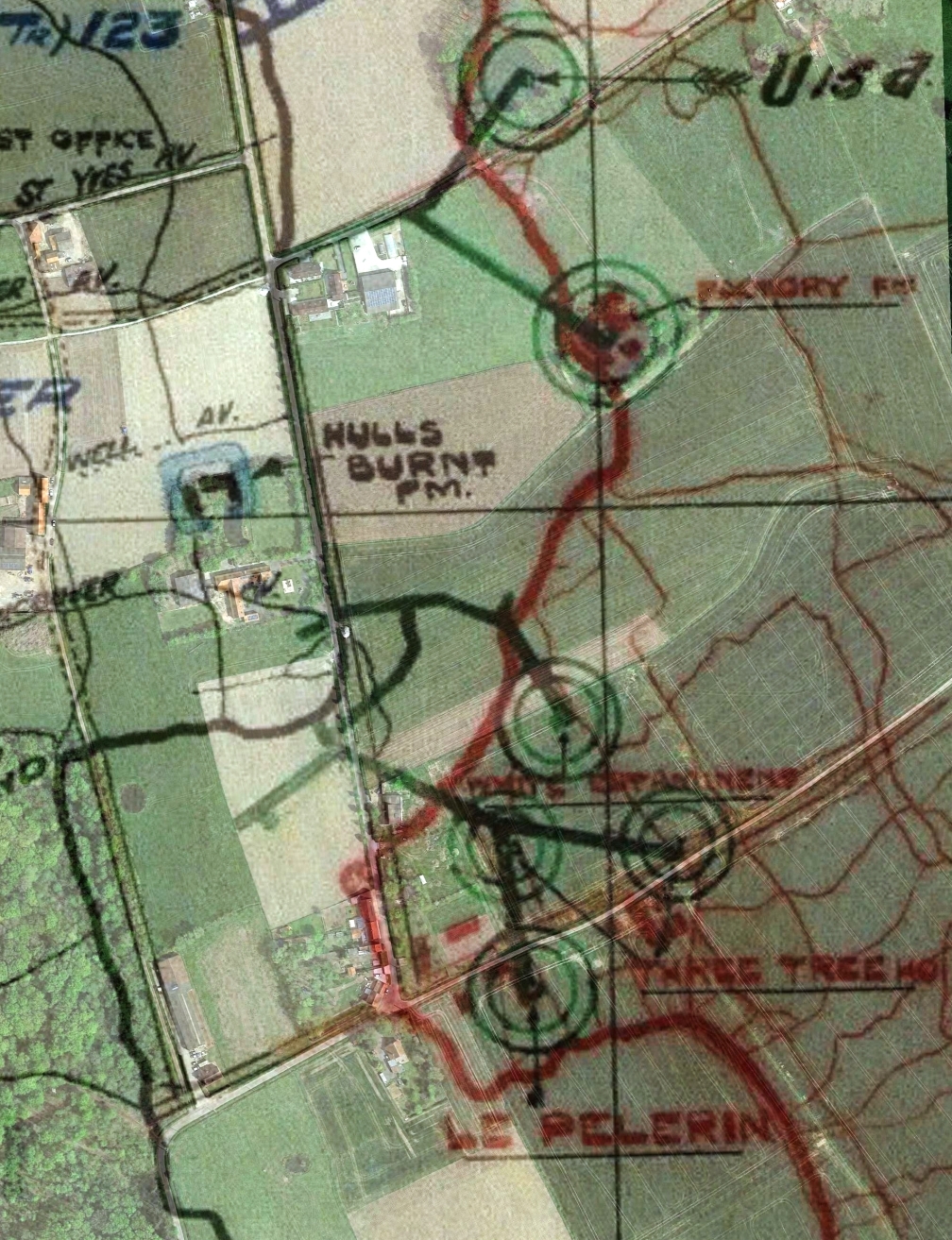

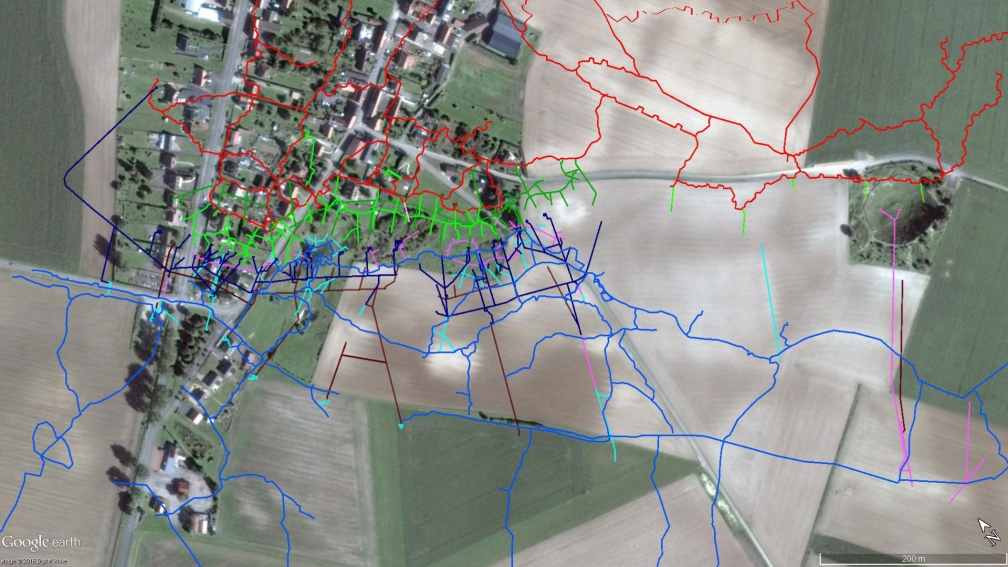

The cluster of four Birdcage mines on a British plan. The German trenches are red, British galleries green, British front line black, over a modern aerial photograph. To the north are the Factory Farm and Trench 122 mines which were fired in the battle. (WO153/909 The National Archives /GoogleEarth)

When the new attack was ordered for June 1917, the four mines were not required but were kept in readiness. The 3rd Canadian Tunnelling Company had taken over the mines from 171st, and Lieutenant B C Hall was immediately ordered to inspect the Birdcage galleries to ascertain whether the mines could be blown in case of counterattack. Exhausted after the successful detonation of two mines nearby, he found the shaft damaged but was able to climb to the bottom. He found the detonator leads to be intact but, looking down the gallery, he could see that the timber props had all splintered in the middle, giving it the appearance of an hourglass or letter ‘X’. He was just able to squeeze through by crawling along the lower portion of the X, recalling that:

The going was very slow, extremely hard work and it was stiflingly hot.

He reached a point 400 feet beneath no man’s land, where the tunnel branched, but could go no further and with difficulty managed to turn around.[2] Two weeks later, the War Diary of the 3rd Canadian Tunnelling Company reported that the tunnels were being kept dry by pumping and baling but that the charges were not likely to be used.[3]

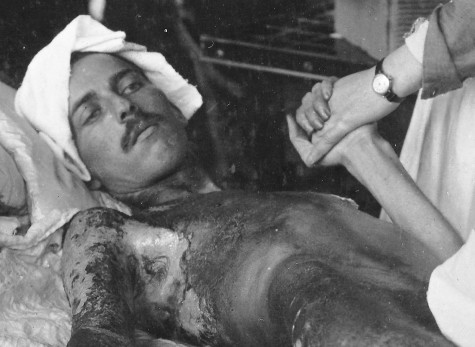

Tunnellers excavate a dugout in the Ypres Salient. The mine galleries were much smaller than this. (Australian War Memorial E01513)

How Lost were the ‘Lost’ Mines?

Two other mines were laid for the Battle of Messines but were ‘lost’ when it proved impossible to maintain access to them, owing to German activity and the extremely difficult geological conditions. The secret of the Messines mines was that they were laid in clay, known as ‘blue clay’, or a mixture of sand and clay, known as Paniselien or ‘bastard’ clay, which were impermeable to water. The thick bands of clay around 70 to 150 feet below ground are the cause of the high water table and waterlogged sands in Flanders. If a shaft could be sunk through the wet sand into the clay, then dry tunnels could be dug, but sinking a shaft required both great experience and special steel caissons or tubbing to keep out the tremendous pressures. Once a horizontal gallery was begun in the dry clay, there was still a danger of the clay membrane above breaking and the whole gallery flooding with a sudden inrush of sand and water.

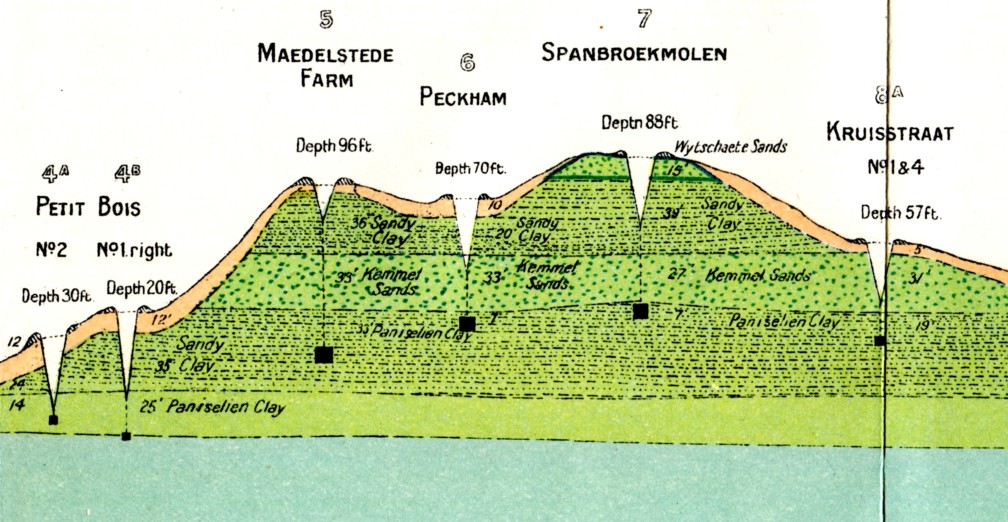

The central of the nineteen Messines mines in the geological section shows how they were laid in the Paniselien or ‘bastard’ clay, close to the running sand and above the deeper blue clay.

Lost through enemy action: the La Petite Douve mine

The shaft for a gallery aimed at a German position in the ruins of La Petite Douve Farm was started by the 3rd Canadian Tunnelling Company in March 1916. It was taken over by 171st Tunnelling Company who with much difficulty managed to sink it to 80 feet depth and drove a gallery 865 feet beneath the ruins. In mid-July they charged it with 50,000 pounds of explosives, then ran a branch tunnel to the left to prepare a second charge chamber. The Germans were suspicious and sank two shafts to search for the British tunnels but lined them with timber not steel, through which the water constantly forced its way in. On 24 August the British heard the Germans working so close to their branch gallery that they seemed about to break in. To have fired a charge to destroy the German working would probably also have detonated their main charge, and so 171st laid a small charge sufficiently large to rupture the clay membrane which would flood the workings with water and sand but leave their main charge intact. They could hear the Germans clearly, laughing and talking, and on 26th detected them breaking into the chamber where they had laid the smaller charge. The British immediately detonated it, killing nine Germans underground and sending a large cloud of grey smoke up the shaft in the German positions. The main British charge was undamaged and 171st laid a 1,000 pound charge in the branch gallery ready to blow again. However, the Inspector of Mines at GHQ was concerned that this would escalate underground warfare in the sector and lead to the loss of the main charge. The Germans did retaliate with a heavy charge two days later which smashed 400 feet of the main British gallery and killed four men engaged in repairs. It also cut off access to the 50,000 pound charge but, as it was clear to the British that further activity was pointless, 171st was forced to abandon the gallery and the mine became ‘lost’.

La Petit Douve mine on a British plan, top left. The German trenches and the farm ruins are red and the British galleries in dashed green, over a modern aerial photograph which shows the location of the rebuilt farm slightly to the north. (WO153/909 The National Archives /GoogleEarth)

Lost to quick sand: the Peckham branch mine

The liquid wet sand was also particularly troublesome at a drive towards a position at Peckham Farm to the south. When the clay was exposed to the air it swelled with such force that it splintered the usual supports, necessitating the use of 7″ x 7″ timbers. After driving a gallery, started in December 1915, 1,145 feet beneath the farm the British laid a charge of 87,000 pounds, then attempted to drive branch galleries to a second objective but twice had to abandoned them, the Tunnellers escaping with their lives from the rapid inrush of water and sand. The third attempt appeared more successful until the ground again gave way. Eventually however, a 20,000 pound charge was laid by creating several small chambers. When the electric pumps broke down, access to the large and small charges was lost and the gallery had to be re-dug for 1,000 feet, with steel joists now replacing the wooden timbers, until eventually in March 1917 connection was again gained with the larger charge. The smaller charge however was judged to be too difficult to regain and was abandoned.

The Peckham mine crater and the ‘lost’ mine to the northeast. The German trenches and farm ruins are red and the British galleries in green, over a modern aerial photograph which shows the location of he rebuilt farm on top of the unexploded mine. (WO153/909 The National Archives /GoogleEarth)

How Dangerous are the ‘Lost’ Mines?

The Messines charges were carefully waterproofed by packing the explosives in tins covered in tarred canvas. The detonators were sealed in bottles and the leads protected by rubberised canvas hoses inside coiled steel. It was perhaps this armoured hose running up to the surface that carried the electrical current to the detonators of one of the Birdcages charges 65 feet below ground, from a lightning strike nearly forty years after it was laid. It caused the detonation of the easternmost of the four mines but thankfully the only casualties were cows, an electricity pylon and some roadway. The other three Birdcage mines still lie nearby beneath the former battlefield. After the war La Petite Douve Farm was rebuilt about 100 yards to the north of the location of the old farm, still uncomfortably close to the abandoned 50,000 pound mine. The farm close to Peckham mine was rebuilt 100 yards to the northeast, exactly over the location of the ‘lost’ 20,000 pound mine.

The location of this warning sign is not known but it may have been placed over the Birdcage mines after the Battle of Messines. (Australian War Memorial H15258)

See below for the notes to this article.

Join me on a battlefield tour with The Cultural Experience: Tunnellers on the Western Front: The Underground War, 15th-18th September 2023

The Story of the Lochnagar Mine

Join me on a battlefield tour with The Cultural Experience

The Battles of the Marne & the Aisne 1914 – 1918

First & Last Shots 1914 & 1918

Medics & Padres in the Great War

More Information about Battlefield Tours

Understanding Chemical Warfare in the First World War

Notes

[1] Sources used for this article may be found in my book Underground Warfare 1914-1918 (Barnsley 2010).

[2] B. C. Hall, Round the World in Ninety Years, (Lincoln, 1981), p. 66.

[3] War Diary 3rd Canadian Tunnelling Company, 22/6/1917, Library and Archives Canada [accessed 30 April 2017].

Detail from geological section of Second Army Offensive Mines 7/6/1917 from The Work of the Royal Engineers in the European War, 1914-19. Work in the field under the Engineer-in-Chief, B.E.F., Geological Work on the Western Front, (Institution of Royal Engineers, Chatham, 1922)

Myths of Messines: ‘The Big Bang Heard in Downing Street’

More articles on the Home page.

Another very interesting and informative read. I love the photo ‘don’t camp here’! Thanks Simon

Excellent article. I never realised there we actually five mines still missing.

THERE are many mines and bombs being found and dug up by farmers while mowing their fields in East and West Flanders and they are put to the edge of the fields to wait for the Belgian army bomb disposal unit to come along to see if they are a danger to the public and if they are they detonate them in a safe place. and if the mine or bomb is of a big or large size they come along and detonate it or them straight away.

I live in East Flanders not far from The American First World War Cemetery in West Flanders i live not for from the border of the two Provinces

I

Your petit douvre modern area is the incorrect location. What you have is just outside Mesen. I could give you the correct location for the overlay if you like? Would be interesting to see.

Ben

Ben, Yes please, I’m intrigued to learn how it is incorrect. Simon

I remember years ago reading an article about the mine that exploded in 1955, caused by a lightning strike, the current following the steel conduit down 65 ft. underground causing the mine to detonate, just goes to show those old tunnellers knew their trade. I’ve never been there to see it but apparently it left a massive hole in the ground which is now filled with water, we now have those other lost mines which pose the same hazard.