© Vincent Faupier.

In Ivor Gurney’s poem about his experiences in the First World War ‘The Silent One’, the musician and poet describes a failed night time attack in which a non-commissioned officer is killed and left hanging on the uncut barbed wire. With the attack held up, Gurney is politely asked by an officer to try to get through a possible gap in the wire but, with equal politeness, he declines.

The poem has been described by his biographer as ‘this most truthful report from the battlefield’.[1] Although he was writing in the 1920s, the preciseness of the details suggest that Gurney was recalling an actual event. In 2010, while I was guiding a group on a literature-themed tour of the Western Front, we visited the place where Gurney was wounded during an attack on the night of 6th – 7th April 1917 and we realised that this was clearly the event that Gurney was describing in ‘The Silent One’.[2] It was one of many minor attacks made by the British as they pursued the German withdrawal from the Somme battlefield to the Hindenburg Line. Typically the Germans held positions for a few days, inflicting casualties with machine guns, before pulling back. The British attack had been planned for two days earlier only to be cancelled. Every such attack required soldiers to prepare themselves mentally for death or wounds and Gurney described his feelings to his friend Marion Scott:

My state of mind is — fed up to the eyes; fear of not living to write music for England; no fear at all of death.

He hoped a ‘Nice Blighty’ would come soon, by which he meant a wound serious enough to require treatment in the UK.[3] A fortnight after the attack had taken place, Gurney wrote again to Marion Scott, explaining that he was indeed ‘wounded: but not badly; perhaps not badly enough’ for he did not have a Blighty wound but was in hospital in Rouen.

It was during an attack on Good Friday night that a bullet hit me and went clean through the right arm just underneath the shoulder…[4]

Ivor Gurney in Rouen while recovering from the wound in his right arm received during the attack of 6- 7 April 1917. (The First World War Poetry Digital Archive, University of Oxford (www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit); © The Ivor Gurney Archive, Gloucestershire Archives).

Part of Ivor Gurney’s service record showing the date of his wound on 7 April 1917, the abbreviation indicating ‘gunshot wound right arm’. (National Archives WO363 via Findmypast.com).

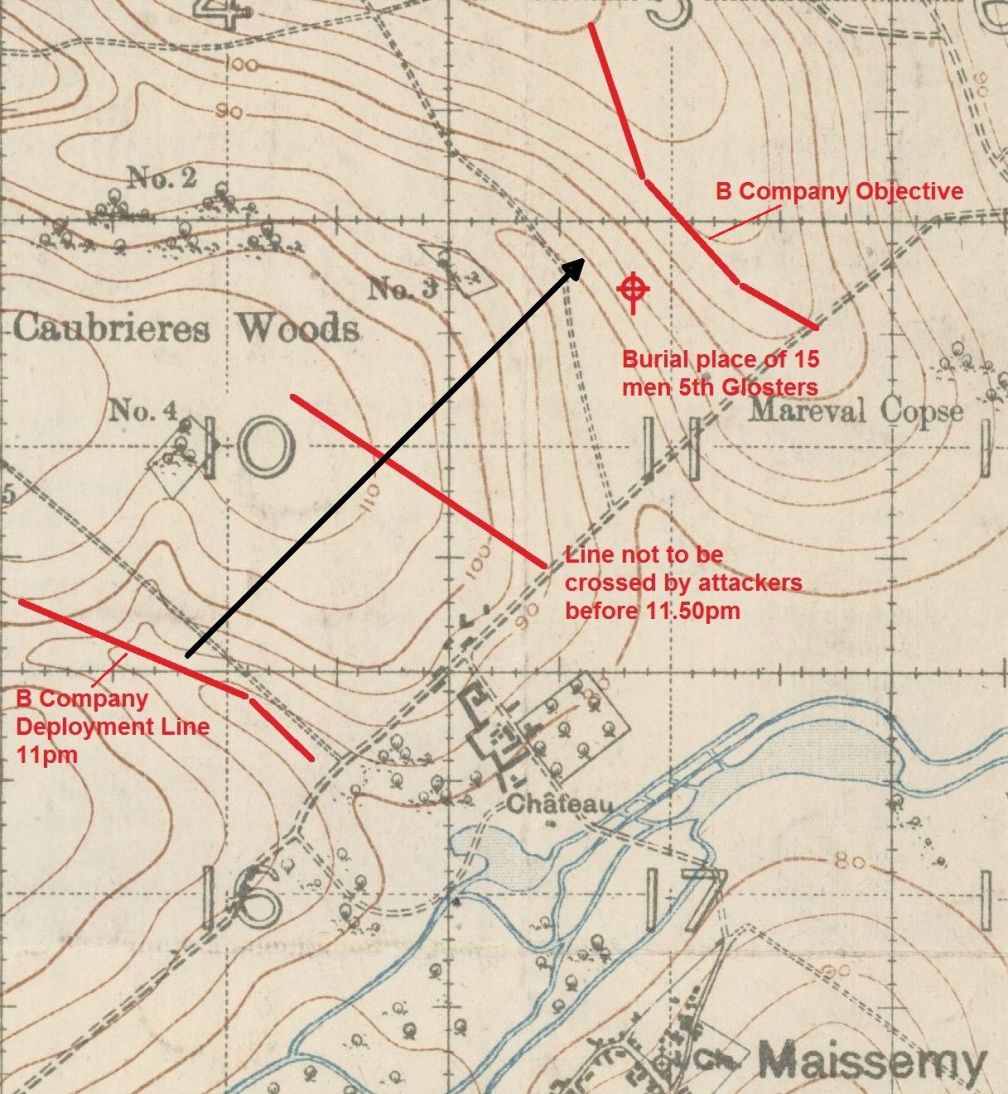

The attack was made by two battalions of Gurney’s Brigade. On the left was the 4th Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry while on the right was Gurney’s battalion, the 2/5th Gloucestershire Regiment. The Glosters (as they were known) attacked with two companies, Gurney’s B Company was on the left and C Company on the right. The 59th Division was also supposed to attack to the left of the Ox and Bucks.

The right of the position along which the 2/5th Glosters deployed for the attack on the night of 6th April 1917, about 1,000 yards from the German positions. Neither the farm nor the cemetery were there at the time. (GoogleEarth).

The Germans held trenches along high ground, protected in front by belts of barbed wire which were concealed from British observation by a depression. The speed of the German retreat left the British without maps of the German positions and this lack of information contributed to the failure of the attack.[5] On the night of 6th, Good Friday, the attackers moved forward to a position about 1,000 yards from the German positions. The night was wet and very dark with no moon. Their orders were to deploy by 11pm and they will have lain down and waited for the British guns to open up. Gurney’s B Company occupied a line about a third of a mile in width.

British Trench Map with the attack of 6th-7th April 1917 marked. This map, corrected to 30th January 1917, did not show the German trenches or wire; woods are also incorrectly plotted. (Map: McMaster University Creative Commons).

At midnight, the artillery began a forty-minute bombardment of the German positions, building to an intense fire for the final five minutes. The Brigade commander afterwards stated that the British shells fell short but there were no reports of any British casualties from this cause. At 12.40am two companies from each of the two battalions rushed forward and the British guns advanced their targets by 100 yards every four minutes: this formed a ‘creeping barrage’ that the attackers were supposed to follow.

Lieutenant Brown, of the Ox and Bucks attacking to the left of Gurney’s Company, said that his men started ‘in quick time’; as they neared the German positions, they broke into a rush towards the wire and some were shouting. There were shouts heard also from the Germans and two or three were seen to climb out of their trenches and run away. But the attackers did not see the German wire until they were right on it: they found that the shelling had missed it, it was uncut, about ten yards deep and about five feet high. The Germans at once targeted their wire with machine guns and grenades, in the darkness sparks flew where the bullets hit. Brown reported that his own light machine guns were unable to suppress the German fire; consulting with Gurney’s Glosters on his right, he found that they were also held up.

Gurney’s men too had found the wire uncut: Lieutenant Pakeman was reported in the Glosters’ War Diary to have:

rallied his men and made 3 efforts to get through, though himself wounded. He led his men up to the wire & cut a certain amount himself.

Pakeman was to be awarded the Military Cross for his part in the unsuccessful attack, the citation recording that:

He led his company in the most gallant manner and personally tried to cut gaps in the enemy’s wire. Later, although wounded, he remained at his post.

The War Diary also mentions that in C Company, Sergeant Davis ‘distinguished himself cutting a gap large enough for 5 men to get through. All of whom were killed.’ This man was Lance-Sergeant Frank Davis, awarded the Disguised Conduct Medal with the citation:

He led his platoon in the most gallant manner, and personally tried to cut a gap in the enemy’s wire. He was severely wounded.

The area attacked by the Glosters. The German trenches were just beyond the crest line which is marked by trees on the right. The German wire was above and behind the area of trees in the middle ground (Cooker Quarry). The track is where the Glosters and Ox and Bucks withdrew before their second attempt to get through the wire. (GoogleEarth).

These attempts to get through the wire were fruitless and the two battalions withdrew to a partially sunken track to reorganise.[6] Brown again spoke to the commander of the Glosters’ B Company and they decided to make another attempt to get through the wire. Taking place at about 1.30am, this also failed and they withdrew to the track. This withdrawal and failed second attempt is described by Gurney’s two final lines:

retreated and came on again,

Again retreated a second time, faced the screen.

Brown again conferred with the two Glosters company commanders and an officer of the 59th Division to his left: none had got through the wire and they decided to withdraw on the grounds that it appeared impossible.[7]

2/5th Glosters War Diary entry for 7 April 1917. (National Archives, WO95/3066).

The 2/5th Glosters’ War Diary records that 15 men were killed from the battalion, and seven officers and 27 men wounded, including Lieutenant Pakeman. Six of the wounded were evacuated, one of whom will have been Gurney.[8] The bodies of the dead, originally buried near to the German wire, were moved to Vadencourt British Cemetery in 1919.[9]

A German cemetery is now on the site of the German trenches attacked by the Glosters. This view looks back across the ground over which they advanced and shows the dead ground in front of the German positions which apparently prevented the artillery from bombarding the German wire. © Vincent Faupier.

The German resistance was part of a holding operation and when more British troops repeated the attack, on the night of the 8th – 9th April, the Germans were found to have withdrawn. A study of this short battle suggests that Gurney’s recall of events was precise and accurate and that his capacity for intense self-examination provides valuable insights in respect of his admission of his refusal to attack and the way that this was apparently accepted by his superior officer. Such disobedience of an order in the face of the enemy could have resulted in Gurney receiving the death penalty. Instead, the incident appears to illustrate the circumstances whereby, in a heavily civilianised British army, officers preferred to lead by example, rather than compelling their men to carry out a task that they themselves would not. It also suggests circumstances in which orders were a matter of negotiation where disobedience in certain situations would be accepted.

Two individuals are described in the poem. It is impossible definitely to identify the probable officer who unsuccessfully asks Gurney, with ‘the politest voice – a finicking accent’, whether he might find a way through but he may have been Lieutenant Pakeman, decorated for his part in the attack. In 1916, Sidney Arnold Pakeman was a history master at Marlborough College, having graduated from Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. After the war he became Professor of History at the University of Ceylon and died in London in 1975.

It is possible to offer a more confident identification for the other soldier. The poet characterises him by his Buckinghamshire accent and his non-commissioned officer’s stripes:

The opening of ‘The Silent One’ from Gurney ‘Best Poems’ notebook. (The First World War Poetry Digital Archive, University of Oxford (www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit); © The Ivor Gurney Archive, Gloucestershire Archives).

The Silent One

Who died on the wires, and hung there, one of two –

Who for his hours of life had chattered through

Infinite lovely chatter of Bucks accent:

Yet faced unbroken wires; stepped over, and went

A noble fool, faithful to his stripes – and ended.

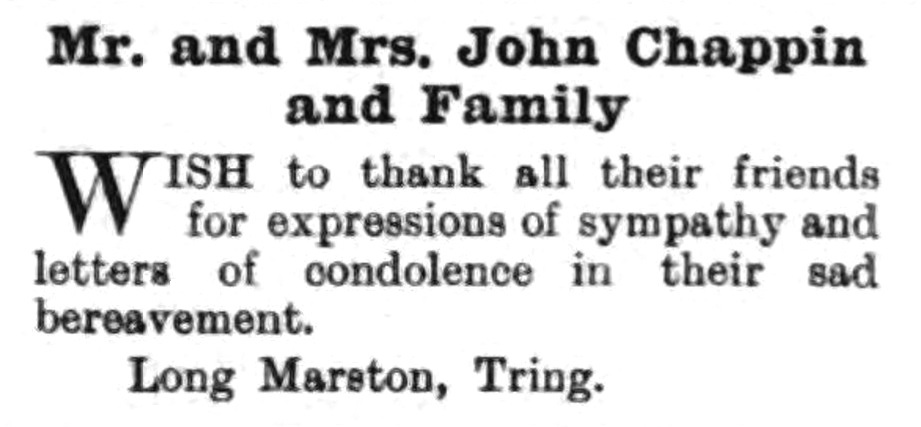

In April 1917 Gurney’s battalion still had a strong Gloucestershire identity and, of the fifteen killed in the attack, all but four were born or enlisted in the county or in Bristol.[10] None was strictly from Buckinghamshire but one, a corporal, was born in Long Marston, Hertfordshire, in an area closely enclosed on three sides by the boundary of Buckinghamshire. It was in the Bucks Herald newspaper that the parents of a dairy worker, Corporal James Chappin, placed two announcements on 26th April 1917:

The Bucks Herald, 26th April 1917 (via FindMyPast.co.uk).

The grave of James Chappin in Vadancourt British Cemetery with the inscription chosen by his next of kin.

The grave of Ivor Gurney in St Matthew’s Churchyard, Twigworth, Gloucestershire (Phillip Dutton).

Text © Simon Jones. See below for Notes.

Join me on a battlefield tour with The Cultural Experience. We cut out delays at Dover by travelling via Eurostar from London St Pancras to meet our coach in Lille:

The War Poets: Words, Music and Landscapes, 6th-9th July 2023

First & Last Shots 1914 & 1918

Medics & Padres in the Great War

Walking the Somme, Summer 2023

More Information about Battlefield Tours

Notes.

[1] Michael Hurd, The Ordeal of Ivor Gurney, (Oxford, 1984), p. 203.

[2] My thanks to Mrs. Joyce Kendell for pointing out the resemblance.

[3] R. K. R. Thornton (ed.), Ivor Gurney War Letters, (London, 1984), pp. 152.

[4] Letter postmarked 14/4/1917, Ivor Gurney War Letters, op. cit., p. 154.

[5] The latest map found is Sheet 62cS.E. Edition 2A Trenches, corrected to 30/1/1917. Later maps (2nd February 1918) shows a series of fire trenches on the crest and forward slope which, if German, would have been there on Good Friday 1917. The positions of small woods are shown incorrectly on the earlier maps.

[6] Brown discovered that the 59th Division on his left had not attacked and its troops were crowding into his sector. See note below.

[7] A report by 184th Brigade states that a third attempt was also held up before the withdrawal was made. ‘Report on attack on German trenches on night 6/7th April, 1917′; ‘Report on Operations carried out by 184th Infantry Brigade from the time of taking over from 183rd Infantry Brigade to the time of relief by 35th Division’; Lieutenant K. E. Brown, (commanding A Company, 4th Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Infantry) ‘Report on attack on German trenches on 6/7th April 1917′, War Diary GS 184 Infantry Brigade, National Archives WO95/3063.

[8] War Diary, 2/5 Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment, National Archives, WO95/3066.

[9] CWGC Burial Return via CWGC.org.

[10] Soldiers Died in the Great War, (HMSO, 1921) digitised version searched via Ancestry.co.uk.

Photograph of Ivor Gurney in uniform and detail of ‘The Silent One’ ms are from the First World War Poetry Digital Archive, accessed April 3, 2017, http://ww1lit.nsms.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/collections/item/6942, http://ww1lit.nsms.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/collections/item/6931.

‘It was in fact pure murder’: John Nash’s ‘Over the Top’

Where and How did Edward Brittain Die?

Edward Harrison, who gave his life to protect against poison gas

Edward Harrison, who gave his life to protect against poison gas