They say they are not going to fire again if we don’t but of course we must and shall do, but it doesn’t seem right to be killing each other at Xmas time. [1]

At Christmas 1914, hundreds of soldiers stopped fighting one another, left their trenches and shook hands in no man’s land. For several days, even weeks, British and German soldiers in Flanders barely fired a shot, helped bury one another’s dead, and even played football together. The 1914 Christmas Truce is felt to typify the attitudes of the men in the trenches who, in contrast to those behind the lines, did not hate their enemies and did not want to fight them. Why is this utterly atypical event believed to give a truer picture of the attitude of the soldiers in the trenches than the four years spent in remorseless, brutal conflict? It is not difficult to understand the appeal of the Truce: in the midst of inhumanity at Christmas time soldiers, inspired by the Christian story, spontaneously stopped fighting and shook hands with their enemies.

Like much about the First World War, the 1914 Truce is an event which in the view of many historians has been popularly misrepresented. In particular, media stories about the Truce show an inability properly to interpret historical sources, which are admittedly often partial or contradictory. In the trenches the individual soldier’s view of events was so restricted that, in places where fraternisation did not take place, soldiers refused to believe that it could have occurred. But as many as a hundred eyewitness accounts prove beyond doubt that many truces really happened, not only in the British-held sector but also that of their French ally.

Who was in the trenches at Christmas 1914?

Soldiers have always arranged truces when it suited them, employing conventions to enable this. In addition, where opposing forces have been in close proximity for a period of time, such as during a siege, unauthorised fraternisation might also take place. By Christmas 1914, the lines of trenches were continuous along the Western Front in conditions that resembled a vast, linear, siege operation. After the German advance through Belgium of August 1914 was halted at the Marne, the Germans attempted to outflank the French and British forces by retreating north, leaving in their wake lines of entrenchments which, by October, reached to the North Sea. The Germans tried to break through at Ypres and failed, with tremendous slaughter, in the bitter fighting of the month-long First Battle of Ypres, 24 October to 22 November, the opposing sides both suffering more than 100,000 casualties (54,000 British, 50-80,000 French and 80-130,000 German). Immediately before Christmas, smaller scale attacks on 18-20 December left many bodies still lying in no man’s land.

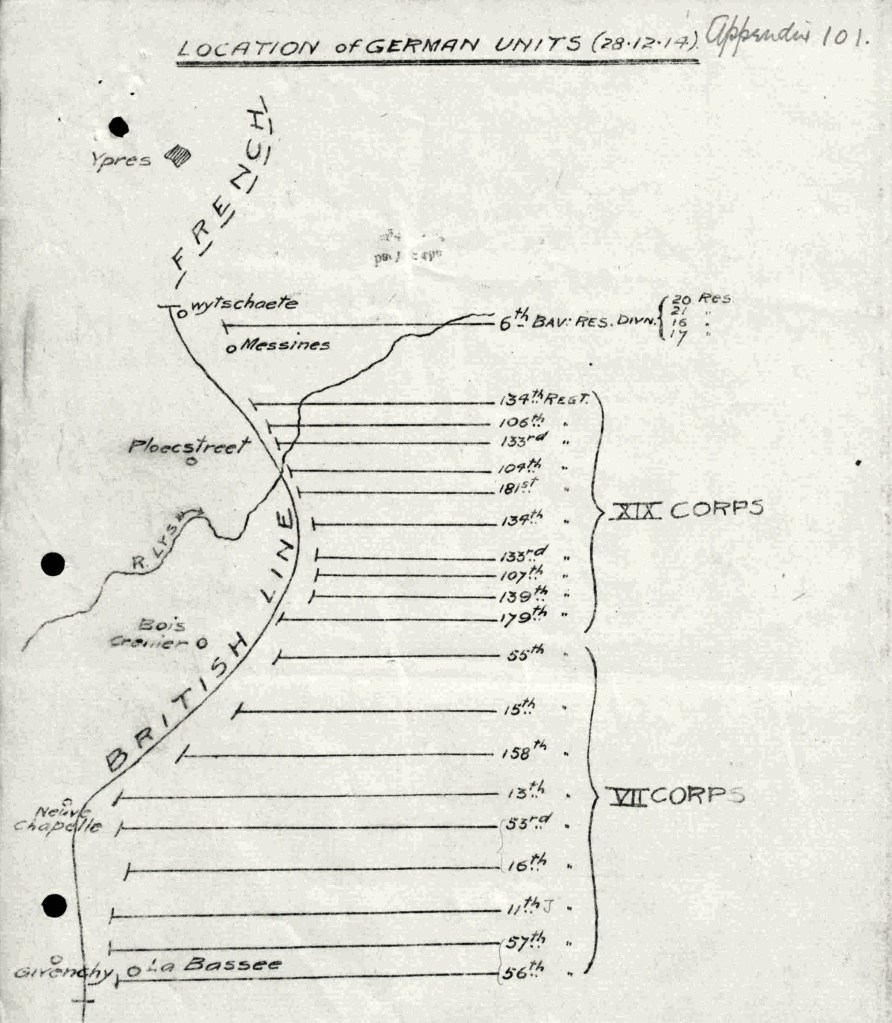

Fraternisation was to take place on two-thirds of the still-small 20 miles of front held by the British, from St Eloi just south of Ypres, to La Bassée. Losses had been such that there was just a comparative handful of survivors left from the fighting of August 1914. Their places had been taken by more Reservists, new recruits and Territorials. Likewise on the German side were Reservists and young soldiers. The British noticed that Saxon and Bavarian troops were more easy-going than Prussians and many of the troops opposite the British where fraternisation occurred were from these state armies.

The commander of II Corps (holding the northernmost five miles), General Smith-Dorrien, anticipated that the static nature of trench warfare and the closeness of the lines in many places might lead the troops to fraternise and on 5 December issued orders to prohibit it:

Friendly intercourse with the enemy, unofficial armistices (e.g. “we won’t fire if you don’t” etc.) and the exchange of tobacco and other comforts, however tempting and occasionally amusing they may be, are absolutely prohibited. [2]

Christmas Eve: Carols and First Contact

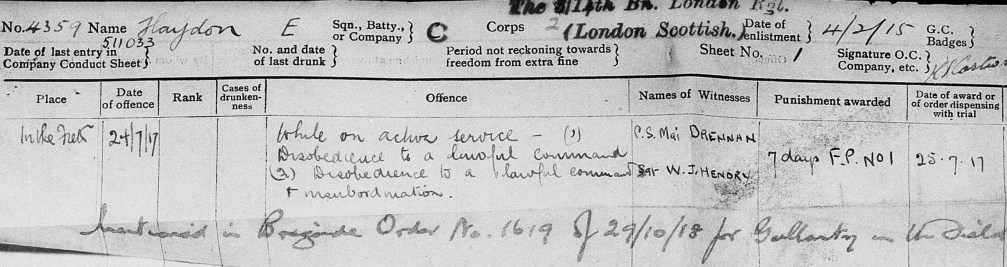

But on Christmas Eve, Smith-Dorrien’s orders were to be ignored or forgotten by many. As firing by sniping and artillery fire died down, fraternisation developed by degrees. As a gesture towards their own troops the Germans sent hundreds of small Christmas trees to their men at the front. When, on Christmas Eve soldiers placed them with lit candles on their trench parapets, in full view of their enemies, it seemed to many wrong to fire on them. Both sides also organised singing in their trenches. Leutnant Johannes Niemann of the 133rd Saxon Regiment was ordered into the trenches on Christmas Eve, and placed a Christmas tree in his dugout and another on the parapet. Then he and his men began to sing Stille Nacht and O du Fröhliche. On the other side of no man’s land, a Seaforth Highlander described how they sang carols and then listened ‘spellbound’ as the sound of German harmonies floated across the turnip field which comprised no man’s land. [3] At one place, however, where the Germans brought a band up to the trenches, it was shelled by British artillery. But mutual carol singing led to calls to meet halfway.

German Christmas tree for troops at the front, 1914-18. (Landeskirchliches Archiv Stuttgart)

A Lieutenant with the 1st Royal Warwickshires, Bruce Bairnsfather (soon famous as a cartoonist), described how in the evening impromptu concerts led to an invitation from the Germans to ‘Come over here!’ at which a Sergeant disappeared into the darkness of no man’s land, out of which they could catch snatches of spasmodic conversation. [4] The 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders witnessed candles being lit on the parapets followed by the singing of Stille Nacht and other carols before an invitation was called across in English by an ex-waiter who had worked in Glasgow. After some light-hearted banter it was agreed that two only from each side should go out but no one else was allowed out of the trenches. One was a young Argylls Second Lieutenant who met a German officer, ‘our conversation was no different from that of meeting a friendly opponent at a football match’ and appropriately enough the German gave him a photograph of his pre-war regimental football team. The Argyll officer gave him a tin of bully beef in return and, after ten minutes, they bid one another a friendly farewell. [5] Not all responded to overtures but many made arrangements to meet on Christmas Day. The Queen’s Westminster Rifles were suspicious at first but, after the Germans lit fires and songs were exchanged, some men ventured out. The established convention for a soldier under cover of a white flag of truce was for him to be brought into the lines blindfolded, in order that he would not learn anything of military use so that he might returned to his own lines. This precaution was forgotten in the case of a German who approached the Westminsters on Christmas Eve and had to be made a prisoner, about which he was ‘awfully upset’. The next morning however three of the Westminsters were also missing and it was discovered from the Germans that they had wandered drunkenly into the German trenches and had also been captured. [6]

Bruce Bairnsfather illustrated his detailed account of the truce with this cartoon in his 1916 memoirs ‘Bullets and Billets’ and captioned it: ‘A memory of Christmas, 1914: “Look at this bloke’s buttons, ‘Arry. I should reckon ‘e ‘as a maid to dress ‘im” ‘

Not everyone in the trenches wished to meet the enemy. An officer of the Rifle Brigade was disgusted to find the German trenches ‘looking like the Thames on Henley Regatta night’. He was in no mind to allow them to enjoy themselves, one of his men having been killed that afternoon, but his Captain, who had seen less of the fighting, wouldn’t let him fire. However, as soon as a shot came from the Germans, he lined his men up and ordered them to shoot away their Christmas trees. When two other officers on the right got out of the trenches and met two Germans halfway across no man’s land, he regarded it as ‘an awfully stupid thing to do’ by those who hadn’t yet ‘seen the Germans in their true light’. [7] But many joined gladly. Two officers of 1st North Staffordshires who walked across to meet the German commander were asked by him for permission to bury his dead in no man’s land; they agreed on condition that only those who were there for that purpose would be permitted. [8] The burial of the dead was for many the real justification for the Truce.

Christmas Day: Peace Breaks Out

On Christmas morning early fog dispersed to reveal a clear blue sky, in only a few places remaining thick until midday. Bruce Bairnsfather recalled that it was ‘just the sort of day for peace to be declared’. [9] In places the Germans put up boards on the trenches reading ‘Merry Christmas’ or ‘You no fight, we no fight’. Officers told their men not to shoot unless it was absolutely necessary and once one side ceased fire, the other followed. The quiet was described by an officer as unfamiliar:

The silence seemed extraordinary after the usual din. From all sides birds seem to arrive, and we hardly ever see a bird generally. [10]

Where the fog suddenly cleared, men of both sides could be seen running about in the open trying to keep warm, behaviour which at any other time would have been suicidal. They waved to one another, and soon were meeting. British accounts tend to give the Germans credit for initiating contact, whereas many German accounts say that the British came out first. Soldiers variously describe the experience as ‘wonderful’, ‘the greatest thing took place here’, the ‘most extraordinary celebration of [Christmas] that any of us will ever experience’, ‘one of the most extraordinary sights that anyone has ever seen,’ ‘While you were eating your turkey etc., I was out talking and shaking hands with the very men I had been trying to kill a few hours before!! It was astounding!’ For Bairnsfather, ‘there was not an atom of hate on either side that day’.

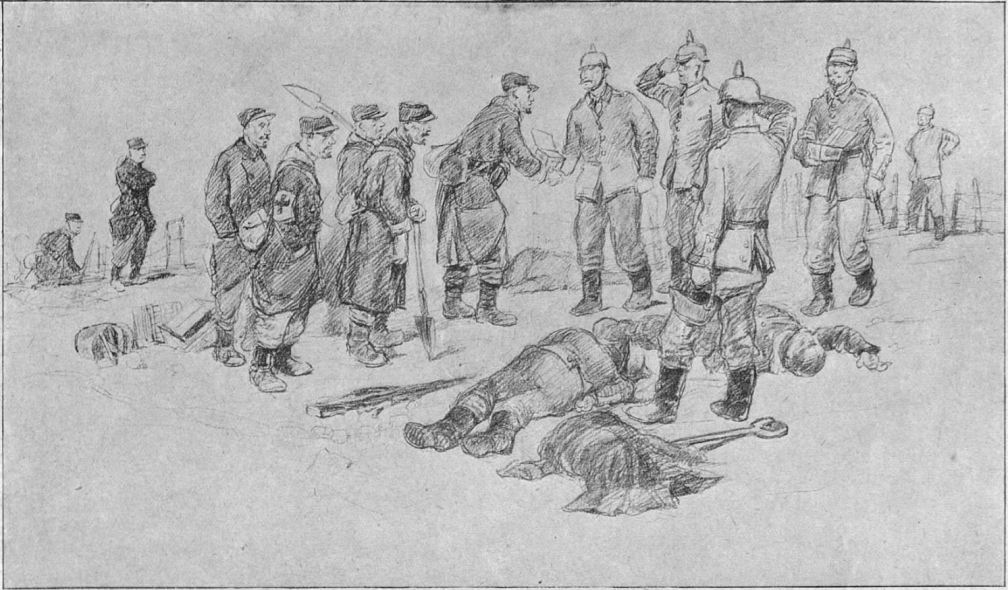

Simple pragmatism was the most powerful impetus to stop firing at one another. The officer of the Rifle Brigade who shot down the Christmas trees the night before now found himself arranging burials with the enemy in no man’s land, justifying it on the grounds that they were not the militaristic Prussians but the more sympathetic Saxons. Together they buried the bodies of nine German soldiers in no man’s land:

We gave them some wooden crosses for them, which completely won them over, and soon the men were on the best of terms and laughing. [11]

Burial of the dead was the main activity in many areas where truces occurred, an unpleasant but important duty to soldiers on both sides. In the largest joint burial, 100 were interred and an officer of the 6th Gordons described ‘a most wonderful burial service’ in which the Germans formed up on one side of the grave and the British on the other, while the 23rd Psalm and prayers were read first in English and then in German. [12] But although the burial and ceremony were conducted jointly, there was still suspicion: afterwards one private showed another a dagger he had kept concealed, adding ‘I don’t trust these bastards’. [13] Burial was perhaps the most poignant of the shared activities, but at least one officer (himself part-German) said that the experience of seeing the dead of their own side left them with a stronger hatred of the Germans than before.

British and German troops burying their dead in no man’s land on Christmas Day 1914, Bridoux-Rouge Banc sector, Flanders. Photographed by Harold Burge Robson of the Northumberland Hussars (Cropped IWM Q 50720).

Officers from both sides tried to get a good look at their opponents’ positions to gather intelligence, noting in particular the locations of machine guns and snipers, and were on the lookout for the enemy trying the same thing. As more men went into no man’s land it was difficult to keep them from crossing a halfway line. When Henry Williamson (a nineteen year old private in the London Rifle Brigade) was turned back from the German lines his officer told him not to do it again. Some who got too close to their opponents’ trenches were taken prisoner, as had occurred with the Westminsters. Both sides did manage to gain sight or even access to their opponents’ trenches and return safely. A British officer described how he had a cigar with a sniper who claimed to be ‘the best shot in the German Army, who said he had killed more of us than any dozen others’. But the officer had located the sniper’s firing position and planned to shoot him the next day.

British soldiers of the London Rifle Brigade meeting German troops of the 104th or 106th Saxon Infantry Regiments, in no man’s land, Christmas Day 1914. (IWM Q 11718)

Another major value of the truces was the opportunity for both sides to improve their trenches and dugouts during daylight without having to worry about exposing themselves to sniper fire. The chance to improve the appalling winter conditions was welcomed where, in the rudimentary trenches, the high Flanders water level meant that digging down more than a few feet met water. Sometimes tools were even shared, as both sides made the most of the chance for improvement works while in some places the cease fire proved so advantageous that it continued into the New Year.

Even in places where there were no dead to be buried, no man’s land was quickly swarming with men ‘shaking hands and wishing each other a happy Christmas’. They swapped badges and buttons, Germans offered cigars, the British gave them foodstuffs, bully beef or jam, in return, even hair cuts were provided. At lunchtime many soldiers returned to their lines to eat, but the 6th Cheshires killed a pig and cooked it in no man’s land. Some of the 2nd Royal Welch Fusiliers were given a barrel of beer by the Germans, for which they offered a plum pudding in return. The beer, from a French brewery just behind the German trenches, was so poor that the British shelled it a few days later.

One reason for fraternisation was simple curiosity, they just wanted to look at the men that they had been fighting. Many British were surprised to find that some at least of the Germans were ‘very nice fellows.’ Many of the Germans had worked in Britain before the war, especially as waiters. The soldiers good-naturedly discussed their respective causes and whilst they may have both expressed a desire to stop fighting and to go home, they remained implacable enemies. Conversation with Germans revealed them subject to propaganda, some believed that London was already occupied by them, others were ‘fed up’ with the war and, the British reported, were realising that they had been ‘bluffed’. One told a Corporal in the 6th Gordons that ‘the war is finished here. We don’t want to shoot.’ An officer of the 1st Royal Warwicks wrote home to say ‘The Germans are just as tired of the war as we are, & said they should not fire again until we did.’ A Staff Officer compiling the War Diary of the 15th Infantry Brigade reported the outcome of conversations: ‘Little mention of the war was made. They expected it to finish within 2 months at least.’ Significantly, the truces were accompanied by only a small number of desertions by either side.

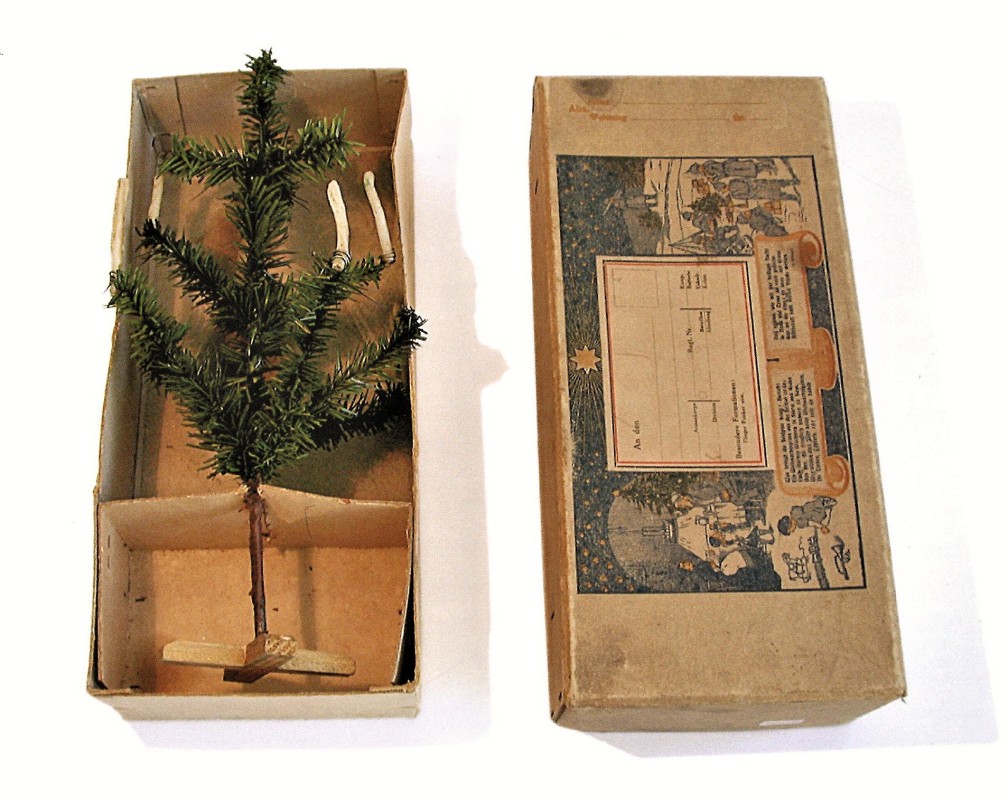

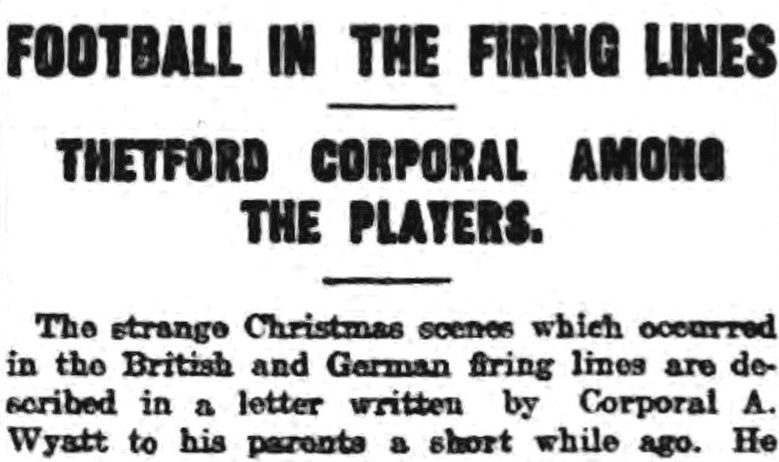

The Thetford and Watton Times, 13 February 1915.

Who played Football?

An activity which has come to capture the popular idea of the Truce, supposedly symbolising the fraternal and unwarlike spirit of the soldiers at the front, is football. Many descriptions of it contain references to the intention to play football, or to football being played elsewhere. For example, the commanding officer of the 1st Grenadier Guards said that the Germans wanted to play them on Boxing Day but that unfortunately they couldn’t supply a ball. Some soldiers played football among themselves, as they took advantage of the lack of firing to play behind or even in front of their trenches, the chance to keep warm being a major impetus.

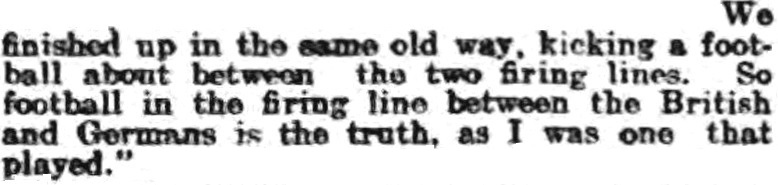

Perhaps remarkably, out of a large number of references to football in hearsay or intending to be played, there are direct, reliable accounts of just two instances of British and Germans actually playing together. Several British sources can be accepted as eyewitness accounts for a game just in front of the German-held village of Messines (Mesen), south of Ypres. Ernie Williams of the 6th Cheshires recalled in 1983 that no man’s land in his sector was not as broken up by shellfire as in other places. He said that the Germans produced a ball and there was ‘a general kickabout’ with ‘about a couple of hundred taking part. I had a go at the ball… There was no referee, and no score, no tally at all.’ [14] That nearly seventy years had passed when Williams’s recollections were recorded has cast some doubt on the reliability of his account. However, a letter from a Sergeant-Major in the same battalion, Frank Naden, was published in a local newspaper which referred to football ‘in which the Germans took part’. [15] The 6th Cheshires was attached for duty in the trenches to the 1st Norfolks and the recent discovery of another letter, also in a local newspaper, by Corporal Albert Wyatt of this unit provides even clearer evidence: ‘We finished up in the same old way, kicking a football about between the two firing lines. So football in the firing line between the British and Germans is the truth, as I was one that played.’ [16] Ideally, there would be confirmation from the opposing troops in the sector, but none of the German accounts from the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment at Messines makes any reference to football.

Letter from Corporal Albert Wyatt, 1st Norfolks, The Thetford and Watton Times, 13 February 1915.

A more organised game of football is described by two members of the same German regiment in a different sector, in accounts which both originate from the late 1960s. Lieutenant Johannes Niemann, of the 133rd Saxon Infantry Regiment described a match for a 1968 BBC television programme:

Suddenly a Tommy came with a football, kicking already and making fun, and then began a football match. We marked the goals with our caps. Teams were quickly established for a match on the frozen mud, and the Fritzes beat the Tommies 3-2. [17]

A letter to Niemann from another member of the regiment, Hugo Klemm, confirmed that football was played. [18] Niemann further stated that they played against Scottish soldiers who they noticed, as their kilts flew up, wore no underpants. [19] The only kilted British regiment facing Niemann’s was the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, but none of the accounts of the Truce from its members, including one by a professional footballer, describes football being played. [19]

Finding clear evidence of the same game from both British and German sources remains elusive. An anonymous letter printed in The Times, in which the writer stated: ‘The — Regiment actually had a football match with the Saxons, who beat them 3–2!!!’ is often cited as corroboration for the match described by Niemann, but a more complete version of the letter, which appeared in the Carlisle Journal, gives the German unit as 107th Saxon Infantry Regiment which places it several miles to the south of Niemann’s 133rd Regiment. [20] Thus the accounts that we have from the German side cannot be corroborated from British sources and, although detailed, were written fifty-four years after the event.

Bruce Bairnsfather’s map showing the turnip field where he met Germans on Christmas Day 1914. From his 1916 memoirs ‘Bullets and Billets’ which contain no mention of football during the Truce.

Football is firmly attached to the story of the Truce. Although it was not the intention of those erecting them, two memorials to the event have become the focus for claims that football matches were played in their vicinity. One erected in 2008 at Frelinghien is where the Royal Welch Fusiliers were given the beer but where no accounts refer to football. The other, unveiled in December 2014 by the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA), is at Saint Yvon, immediately north of Ploegsteert Wood, close to where Bruce Bairnsfather recorded in detail his experiences of meeting the Germans. In 2007, footballs appearing at a nearby wooden cross, erected eight years previously by the Khaki Chums who had spent several days over Christmas living in a reconstructed trench, signalled a growing belief that it marked the spot where the ‘football match’ had been played. This belief has taken root so firmly that in December 2014 UEFA placed a memorial at this spot, despite having been given expert advice that the evidence concerning the location was questionable. Two accounts, one German and one British, have however served to reinforce the believe that football was played at Saint Yvon. The first is the diary of a German officer in this sector, Lieutenant Kurt Zehmisch, who describes the Truce and states that:

Soon a couple of Englishmen brought a football out of their trench and a game started. [21]

Accounts by members of Bairnsfather’s unit, the 1st Royal Warwickshires, indicate that they played football amongst themselves in sight of the Germans and this is what Zehmisch appears to be describing, rather than a match between the British and Germans. [22] Bairnsfather’s own account of the Truce published in 1916 made no reference at all to football. [23] In a 1929 magazine article, he claimed that a football match was proposed but, before it could take place, further fraternization was forbidden. However, in a television interview for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 1958, he described how football was actually played, with the implication that he was an eye-witness. [24] If he had seen football between the opposing sides, it would seem plausible that he would have described it in 1916 and in particular would have depicted it in at least one of his many cartoons. The evidence points to him either consciously or unconsciously embroidering the story or speaking generally about what he had heard had happened, rather than what he had actually seen himself.

Opposition to the Truces

It is often implied that opposition to the Truce came only from the commanders behind the lines but there were many actually in the trenches who had strong qualms about participating in the Truce. Significant numbers refused to take part at all, the most common way of preventing fraternisation was to open fire on those making peaceful overtures. The 2nd Grenadier Guards had lost heavily in fighting on Christmas Eve and, when the Germans ‘put their heads up and shouted Merry Xmas’, the Guards shot at them. [25] Likewise a Staff Officer, recording in his diary that strict orders were issued against allowing any truces, expressed his attitude to fraternisation with the enemy, although he may not have been a direct witness the incident that he described:

The Germans did try. They came over towards us singing. So we opened rapid fire on to them, which is the only sort of truce they deserve. [26]

Many men were killed in this way on Christmas Day, sometimes owing to those in neighbouring trenches not agreeing to a Truce, and in a number of instances the Germans apologised where this had happened. The second-in-command of a battalion of British-Indian troops stopped fraternisation by calling his men back in, scolded two of his officers and reported what had occurred to battalion headquarters. But when this resulted in the stopping of their leave, he felt it far too harsh. Both were killed a few months later, before they could return home. A Lieutenant in 1st East Lancashires at Ploegsteert described receiving a signal from battalion headquarters to make a football pitch by filling up shell-holes, and to challenge the Germans to a match on 1st January. He was furious and took no action, except to destroy the signal. [27] The medical officer to 1st King’s Shropshire Light Infantry in a letter home condemned those singing carols and fraternising, claiming that the regiments which had done so had since come to blows with those which had opposed the Truce. [28] After the Royal Welch Fusiliers left the trenches on Boxing Day, having drunk the beer given to them by the Germans, they were shouted at and spat upon by the French women in Armentieres who told them: ‘you boko kamerade Allemenge’. [29]

As night fell on Christmas Day most men returned to their trenches although, in places, singing continued. Where there had been fraternisation, there was in the main no firing during the night. One battalion did open fire on a German who came as far as their barbed wire but decided that he must have been drunk. On Boxing Day, Germans were still to be seen walking on top of their trenches. Efforts were made to bring the situation back to normal, often by firing a few shots into the air, but neither side wished to resume active hostilities. In one place the task of burying the dead was still to be completed. In another, some artillery officers came up to see what was happening, and found both sides repairing their trenches in full view of the other. Light snow falling on Boxing Day turned to sleet after dark. The worsening weather led to flooding which, while it put an end to fraternisation, also saw the persistence of a passive attitude and general lack of hostility which lasted for many weeks.

Senior officers were generally hostile to the truces but not consistently so. General Smith-Dorrien, who had issued the order against fraternisation earlier in December, visited the trenches on the evening of Boxing Day. He didn’t find fraternisation but was ‘considerably disappointed by the state of affairs’ and ‘the apathy of everything I saw’. On his return to his headquarters, reports of Christmas Day truces were waiting for him. He was famous for his temper, thought to have originated with an old wound, and issued an angry memorandum calling for the names of officers and units which had taken part, with a view to disciplinary action. The British Commander-in-Chief, Sir John French, also issued orders to prevent a reoccurrence and called for local commanders to be brought to account. Only in retrospect did he concede that he might have agreed to an armistice, had the question been submitted to him. General Rawlinson, commanding IV Corps, described reports in his diary without apparent disapproval and did not call for punishments. His subordinate commander, General Capper (7th Division) allowed an informal armistice on 26th and 27th specifically to enable dead to be buried and for the clearing of streams and drainage ditches.

On 28th December, the commander of 11th Brigade sent a message to his three battalions in the trenches telling them to make use of the opportunities of the continuing cessation of hostilities to strengthen their defences but not to let the enemy near their trenches. The Germans seem to have taken the same view, however an army order of 29 December forbade fraternisation as high treason. General Smith-Dorrien issued an order on 1 January which was milder but still required court martial for officers or NCOs who allowed fraternisation. Except for the two officers denied leave, no British soldiers appear to have been punished for fraternising with Germans in 1914. The German order meant that there was little or no contact on New Year’s Eve, except the odd deserter or drunk coming over, but where there had been a cease fire this held good. Elsewhere, Germans showing themselves above the trenches were met by small arms or artillery fire.

The benefit of the Truce to the opposing intelligence services is shown by this British map compiled on 28th December showing every German regiment facing its troops (7 Division GS War Diary, UK National Archives WO 95/1634).

The Legacy of the Christmas Truces

Small, isolated truces took place on the Western Front in 1915, 1916 and even 1917 but they were never on anything like the same scale as in 1914. After the war, the idea that it could have ended at Christmas 1914 was expressed by some who experienced the Truce. Major Murdoch McKenzie Wood, a Member of Parliament who had taken part serving with the Gordon Highlanders, stated in the House of Commons in 1930 that, if it had been left to the men at the front, ‘there would never have been another shot fired… it was only the fact that we were being controlled by others that made it necessary for us to start trying to shoot one another again.’ [30] There is little evidence from the time of this view, either from those at the front or at home. In January 1915, a Manchester Guardian editorial replied on behalf of liberal opinion to the question why the men had gone back into their trenches and were, as the newspaper put it, ‘hard at it again, slaying and being slain’: the answer was that ‘there was very much to be done yet – that Belgium must be freed from the hideous yoke that has been thrust upon her…’ This view was shared by most British soldiers in the trenches, not to mention Belgian and French. One former soldier, asked in 1981 whether, if they had had their way, they would have stopped fighting and gone home was adamant that they would not:

We all wanted to win the war and to see the Germans beaten. It was all right just having the truce and meeting the Germans, but as for ending the war, no, that was quite out of the question. In any case we all expected the war would end next spring… [31]

Perhaps the nearest thing to a consensus among soldiers on both sides is that, although they may not personally have hated their enemies, the Truce was only a temporary cessation of fighting. Most were convinced of the rightness of their cause and believed that the quickest way to end the war was to beat their opponent.

Full fraternisation between French and German troops was rarer. This encounter between soldiers burying their dead in no man’s land on Christmas Day, when they briefly shook hands, saluted and exchanged cigars, was described by Emile Barraud of the 39th Regiment to an artist from The Graphic (30 January 1915).

One man who not surprisingly abhorred the Truce was a twenty-five-year-old Corporal in the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment named Adolf Hitler, at least according to the testimony a fellow soldier from 1940. Men from the future Fuhrer’s regiment almost certainly played football with the Norfolk and Cheshire Regiments but Hitler’s duties as a runner at regimental headquarters seldom took him right into the front line. [32] Two and a half miles to the south of Hitler’s Regiment, a nineteen-year-old Henry Williamson did fraternise with the other side. The disconnect between the preceding violence and suffering, and the warmth and fellow feeling of the Truce seemed so unreal to the young soldier as to leave him troubled for the rest of his life. The realisation that both sides thought that they had God on their side and were fighting for right, led him to believe that future conflict could be avoided with the elimination of misunderstandings between the peoples of different nations. A mistaken belief that Hitler had participated in the Truce led Williamson to conceive a misguided sympathy for him which contributed to his support for fascism. [33] In 1946, still deeply troubled by the Christmas Truce, he embarked on what became a cycle of fifteen novels in an attempt to understand his experiences before, during and after the war.

The Christmas Truce, and especially the role played by football, is an object lesson in the interpretation of historical sources, in particular in distinguishing between hearsay and direct eyewitness accounts. The Truce, like many historical events, has been used to support whatever interpretation of the past suits a particular view of the present. The fanciful presentation of the Truce, in drama, literature, popular history and journalism, shows that we need to step back from contemporary preoccupations if we are to gain historical understanding and that, if we want our history to be ‘relevant’, it probably won’t be good history. One soldier looked back on the 1914 Christmas Truce as ‘just a happy dream.’ [34] He did not realize how apt his description was to be.

Scroll down for references © Simon Jones

Buy signed copies of The War Underground 1914-18 and World War I Gas Warfare (Osprey Elite Series)

‘It was in fact pure murder’: John Nash’s ‘Over the Top’

Understanding Chemical Warfare in the First World War

‘Anon.’ no longer: the author of Menin Gate poem revealed

References:

- Private William Tapp, Malcolm Brown and Shirley Seaton, Christmas Truce the Western Front December 1914, (2001), p. 195.

- Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 36.

- John Ferguson, Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 61.

- Bruce Bairnsfather, Bullets and Billets, (1916), pp. 85-97.

- Second Lieutenant Ian Stewart, Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 64.

- Brown & Seaton, op. cit., pp. 65-66.

- Unnamed officer, Brown & Seaton, op. cit., pp. 67-68.

- Captain R. J. Armes, Brown & Seaton, op. cit., pp. 68-69.

- Bairnsfather, op. cit., p. 90.

- Edward Hulse, Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 92.

- Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 84.

- Arthur Pelham-Burn, Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 89.

- Brown & Seaton, op. cit., pp. 90.

- Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 138.

- Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 139.

- The Thetford and Watton Times, 13 February 1915. I was first alerted to this newscutting by Taff Gillingham who obtained it from the Norfolk Regiment Museum.

- Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 136. Niemann also described the football match in a history of his regiment written at the same time, J. Niemann, Das 9. Königlich Sächsische Infanterie-Regiment Nr.133 im Weltkrieg, 1914-18, (1968) p. 32.

- ‘Everywhere you looked the occupants from the trenches stood around talking to each other and even playing football.’ Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 136.

- Chris Baker, The Truce the Day the War Stopped (2014), p. 161.

- The Times, 1/1/1915, p. 3; The Carlisle Journal, 8/1/1915 quoted http://www.christmastruce.co.uk/cumbria/.

- Baker, op. cit., p. 162.

- Taff Gillingham, pers. comm. 15 December 2014.

- Bairnsfather, op. cit., pp. 85-97.

- ‘The American Magazine’, December 1929, p. 145 (I am grateful to Paul Baggaley for drawing my attention to this source); http://www.cbc.ca/player/play/2448571386 (accessed 8/11/2016).

- George Darrell Jeffreys, Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 104.

- Billy Congreve, Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 104.

- C. E. M. Richards, Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 139.

- Tom Ingram, Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 192.

- Frank Richards, Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 154.

- Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 190.

- Graham Williams, Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 192.

- Heinrich Lugauer, Thomas Weber, Hitler’s First War (Oxford, 2010), p. 63.

- Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 193.

- Leslie Walkington, Brown & Seaton, op. cit., p. 192.

Where and how was Edward Brittain killed? The death in action of her brother Edward, in Italy in June 1918, forms the final tragedy of Vera Brittain’s memoir Testament of Youth.

Shirebrook Miners in the Tunnelling Companies

Who was Ivor Gurney’s ‘The Silent One’? The night attack by the 2/5th Glosters on 6-7 April 1917

![British_55th_Division_gas_casualties_10_April_1918[1]](https://simonjoneshistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/british_55th_division_gas_casualties_10_april_19181.jpg?w=605&h=401)

![British_55th_Division_gas_casualties_10_April_1918[1]](https://simonjoneshistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/british_55th_division_gas_casualties_10_april_19181.jpg?w=1008)

![[Gen Charsley] EeAHyX_XgAUZi8x-ROT2-cr](https://simonjoneshistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/gen-charsley-eeahyx_xgauzi8x-rot2-cr.jpg?w=469&h=467)