On the last day of 1914, at the age of forty-one, the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams lied about his age to join the ranks of the Royal Army Medical Corps. He was to serve in the Army for the remainder of the First World War.

Ralph Vaughan Williams with the 2/4th London Field Ambulance at Saffron Walden in 1915. (© Vaughan Williams Foundation)

The experience inspired his Pastoral Symphony, completed in 1922, as an elegy to the dead of the war. In particular, in an often-quoted letter to his future wife Ursula Wood, he recalled that it grew out of his time as a medical orderly in France in 1916:

It is really war time music – a great deal of it incubated when I used to go up night after night in the ambulance wagon at Ecoiv[r]es & we went up a steep hill & there was a wonderful Corot-like landscape in the sunset – it’s not really Lambkins frisking at all as most people take for granted.[1]

Vaughan Williams served with the 2/4th London Field Ambulance, with which he was posted to France in June 1916. The following month it took over a sector of front in the chalk downland of Artois, where it was responsible for evacuating and treating the wounded. This unit was based at the village of Ecoivres, 4.2 miles behind the front line, where it operated a Main Dressing Station, bringing wounded each night from an Advanced Dressing Station.

Scheme for Evacuating Sick and Wounded from 60th Divisional Area (Provisional), 26 July 1916 (detail).[2]

Unlike villages closer to the front line, which were utterly destroyed after being retaken from the Germans during bitter fighting, Ecoivres was largely untouched. Its location close behind the lines made it valuable for billeting troops as well as housing medical and logistic units.

Graffiti left by British and Canadian soldiers on Ecoivres church still bears witness to its role during 1914-18.

The buildings used as the Main Dressing Station are today still the village school.

The Main Dressing Station was located in the former village school. On arrival in July, the officer commanding found it ‘full of sick & wounded not yet attended to or evacuated.’[3] Over the coming weeks, he expanded the facilities, obtaining the use of huts behind the school buildings.

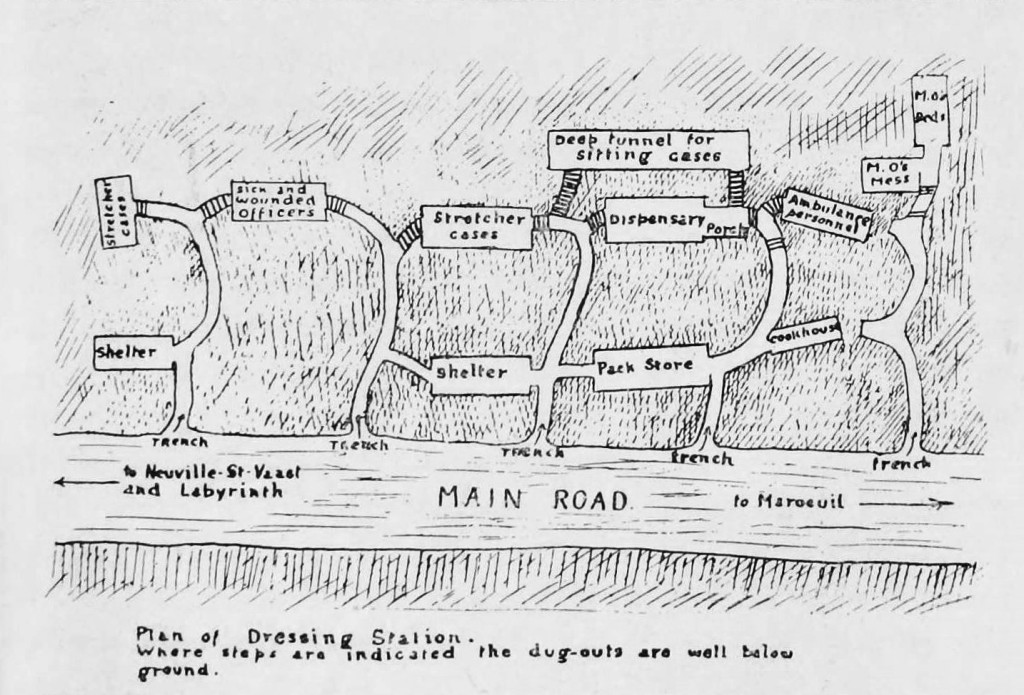

This plan survives in the War Diary of the Canadian medical unit which took over running the Ecoivres Main Dressing Station later in 1916.[4]

The classroom on the right was the sick parade room, on the left was the Orderly Room.

Vaughan Williams’ work collecting wounded was to take him into the valley beneath the German-held Vimy Ridge. Already the scene of heavy fighting during the previous eighteen months, it had become known as ‘Zouave Valley’ after the bodies of French Algerian troops killed trying to take the ridge.

Scheme for Evacuating Sick and Wounded from 60th Divisional Area (Provisional), 26 July 1916.[5]

Each night, under cover of darkness, a convoy of motor ambulances collected the wounded from the Advanced Dressing Station and took them to the Ecoivres. Vaughan Williams described his experience of active service in a letter to his friend Gustav Holst:

I am very well & enjoy my work – all parades & such things cease. I am ‘Wagon orderly’ and go up the line every night to bring back wounded & sick on a motor ambulance – this all takes place at night – except an occasional day journey for urgent cases. [6]

The observation afforded to the Germans by Vimy Ridge made it unsafe to take the motor ambulances across the valley in daylight. The steep hill he later recalled to Ursula was just outside Ecoivres and was followed by a descent into Zouave Valley.

The ambulance route from the MDS to the ADS, the view to the southeast, with the front line on Vimy Ridge to the left (Google Earth).

The devastation of shellfire was localised to the front line and recaptured areas, the area around Ecoivres and much of the journey up to the Advanced Dressing Station made by Vaughan Williams in the summer of 1916 was through countryside closely resembling how it looks today. This contrast, between the ugly destruction and human tragedy of war and the proximity of gentle unspoilt countryside, powerfully suggest themselves as the inspiration for the Pastoral Symphony.

The return journey to Ecoivres, with the ruined abbey of Mont St. Eloi a well-known landmark. (Google Earth).

The Advanced Dressing Station, near a dangerous crossroads known as Aux Rietz, was just over a mile from the front line and had to be located underground to protect against shellfire.

The underground Advanced Dressing Station at Aux Rietz, depicted just before it was taken over by the 2/4th London Field Ambulance.[7]

The site of the Aux Rietz Advanced Dressing Station, beneath the earth embankment on the right (Google Earth).

Today a vast French war cemetery, La nécropole nationale de Neuville-Saint-Vaast, is directly opposite the former location of the Advanced Dressing Station. In the above photograph, La Targette British Cemetery can also be seen in the distance beyond the French nécropole.

Plan of the headquarters buildings in Ecoivres, as taken over by 9th Canadian Field Ambulance in October 1916. [8]

The headquarters, stores and accommodation for the personnel of the 2/4th London Field Ambulance were also situated in Ecoivres, a little way up the main street from the school buildings in a large house which also still survives.

The house and outbuildings in Ecoivres used by the 2/4th London Field Ambulance in 1916.

Vaughan Williams’ memory of a bugler practicing during the war, which he echoed in a trumpet cadenza in his Pastoral Symphony, is sometimes said to have dated from his time at Ecoivres. In fact, he stated later, in a letter to the principal trumpet in the Hallé Orchestra, that he had heard this was while stationed at Bordon, training for the Artillery in 1918.[9]

The 2/4th London was relieved in October 1916 as part of the build-up of Canadian units for the assault and capture of the Vimy Ridge which occurred in April 1917. By this time, Vaughan Williams and the 2/4th London Field Ambulance were serving in Greece.

Further Reading

Stephen Connock, ‘The Edge of Beyond’, Journal of the Ralph Vaughan Williams Society, No. 16 October 1999. https://rvwsociety.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/rvw_journal_16.pdf

[1] Hugh Cobbe (ed.), Letters of Ralph Vaughan Williams, 1895-1958, (Oxford, 2008), pp. 264-5.

[2] War Diary, Assistant Director Medical Services, 60th Division (UK National Archives WO 95/3026).

[3] War Diary, 2/4th London Field Ambulance (UK National Archives WO 95/ 3029).

[4] War Diary, 9th Canadian Field Ambulance (RG9-III-D-3, Library & Archives Canada https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/home/record?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2005074).

[5] War Diary, Assistant Director Medical Services, 60th Division, (UK National Archives WO 95/3026).

[6] Hugh Cobbe (ed.), Letters of Ralph Vaughan Williams, 1895-1958, (Oxford, 2008), p. 109.

[7] David Rorie, A medico’s luck in the war being reminiscences of R.A.M.C. work with the 51st (Highland) Division, (Aberdeen, 1929).

[8] War Diary, 9th Canadian Field Ambulance (RG9-III-D-3, Library & Archives Canada https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/home/record?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2005074).

[9] Letter to Arthur Butterworth, 25 May 1949, Hugh Cobbe (ed.), Letters of Ralph Vaughan Williams, 1895-1958, (Oxford, 2008), pp. 450-1.

Join me on a battlefield tour with The Cultural Experience:

The Battles of the Marne & the Aisne 1914 – 1918

First & Last Shots 1914 & 1918

Medics & Padres in the Great War

Walking the Somme, Summer 2023

In John Nash’s painting ‘Over The Top’ 1st Artists’ Rifles at Marcoing, 30th December 1917, the artist depicted a disastrous attack in which he himself took part. A painting bereft of glory, it remains ‘an acknowledged masterpiece’ of war art.

In John Nash’s painting ‘Over The Top’ 1st Artists’ Rifles at Marcoing, 30th December 1917, the artist depicted a disastrous attack in which he himself took part. A painting bereft of glory, it remains ‘an acknowledged masterpiece’ of war art.

The Italian Front in the First World War at Asiago: Monte Zovetto and Magnaboschi

The Italian Front in the First World War at Asiago: Monte Zovetto and Magnaboschi